Gorichanaz, T. (2019). A first-person theory of documentation. Journal of Documentation, 75(1), 190–212.

Abstract. Purpose: To first articulate and then illustrate a descriptive theoretical model of documentation (i.e., document creation) suitable for analysis of the experiential, first-person perspective. Design/methodology/approach: Three models of documentation in the literature are presented and synthesized into a new model. This model is then used to understand the findings from a phenomenology-of-practice study of the work of seven visual artists as they each created a self-portrait, understood here as a form of documentation. Findings: A number of themes are found to express the first-person experience of art-making in these examples, including communicating, memories, reference materials, taking breaks and stepping back. The themes are discussed with an eye toward articulating what is shared and unique in these experiences. Finally, the themes are mapped successfully to the theoretical model. Research limitations/implications: The study involved artists creating self-portraits, and further research will be required to determine if the thematic findings are unique to self-portraiture or apply as well to art-making, to documentation generally, etc. Still, the theoretical model developed here seems useful for analyzing documentation experiences. Practical implications: As many activities and tasks in contemporary life can be conceptualized as documentation, this model provides a valuable analytical tool for better understanding those experiences. This can ground education and management decisions for those involved. Originality/value: This paper makes conceptual and empirical contributions to document theory and the study of the information behavior of artists, particularly furthering discussions of information and document experience.

Introduction

As documents take on new forms and social roles, the study of what documents are and how they work becomes ever more urgent. The academic field of documentation was once concerned with describing and organizing artifacts of scientific knowledge, narrowly defined. Over the past few decades, scholars have applied document theory to a widening range of lived phenomena, showing how the material, cognitive and sociocultural are intertwined. Documentation is understood to be something not only done only by experts, but by—and to—everyone (Day, 2014). Briet (2006) perhaps had this in mind when she referred to humankind as Homo documentator and called documentation a necessary cultural technique for modern life.

Recent work has discussed that, to more fully understand documentation, we must study it from an experiential perspective (Bruce, Davis, Hughes, Partridge, & Stoodley, 2014; Latham, 2014). This paper builds on prior work in this area to articulate a descriptive theoretical model of documentation suitable for experiential, first-person analysis. It then illustrates the use of this model through presenting a phenomenological study of art-making, understood as a form of documentation.

1 A first-person theory of documentation

1.1 The first-person perspective

It has been established in the philosophy of science that theories (a term I intend generally to encompass theories, models, concepts, etc.) each entail a perspective (Van Fraassen, 2008). As Elgin (2017) explains, theories have indexicality, occlusion and commitment; that is, they represent things from somewhere and toward somewhere, they show some things at the cost of hiding others, and they represent only certain aspects of any phenomenon. Thus, says Elgin, taking on different theoretical perspectives can show familiar things in new ways, opening new possibilities for knowledge and design.

Specifically, Elgin dichotomizes perspective as first-person and third-person, and she argues that some phenomena (e.g., understanding) can come to light only in the first person. Centuries ago, this was one of the central insights of Kierkegaard (2009), who identified a difference between objective truth (communicated results) and subjective truth (ways of understanding and being). This was also the perspective of James (2002), who discussed the need for the first-person perspective in the study of existential matters such as religious experience. To give an example, third-person account of a person in love would describe irrational behaviors, acts of affection and communication patterns; while a first-person account of the same person would try to express the feelings and emotions of excitement and confusion. Of course, words can only approximate the directness of experience. Worth (2008) has suggested that such first-person, or "narrative," knowledge can be effectively shared through stories and poems. To put all this another way, third-person knowledge can show that certain things are the case and how they work, while first-person knowledge shows what things are like.

In document studies, most theorization has been done from a third-person perspective, examining the material and social aspects of documents and ignoring the human experience of creating or relating to documents. Indeed, this observation has been made of human information behavior (see Hartel, 2014b), information science (see Jacob & Shaw, 1998), and sociotechnical research generally (see Kallinikos, 2009). When it comes to information, such an emphasis on the external perspectives may overlook something important. As Norbert Wiener (1954, p. 18) writes, "communication and control [of information] belong to the essence of man's inner life, even as they belong to his life in society." To this end, recent work has connected documentation with the epistemic aim of understanding (Bawden, 2007; Gorichanaz, 2017b), challenged the assumption that a person's physically encountering a piece of information constitutes their becoming informed Ocepek (2018), and described becoming and being informed as a phenomenological position (Tkach, 2017).

To be sure, a small body of literature has begun to explore information experience (Bruce et al., 2014) and document experience (Gorichanaz & Latham, 2016; Latham, 2012, 2014)—that is, to look at such phenomena from a first-person perspective, exploring empirically how people become informed. As research in philosophy has shown, knowing what something is like may have consequences for understanding that thing and for developing theories and systems around it (Jackson, 1982; Nagel, 1974). Further research taking the first-person perspective can contribute to improved information system design (Bruce et al., 2014; Hepworth, Grunewald, & Walton, 2014), as well as more empathic and tactful information professional practice (van Manen, 2014). Thus, in this paper I contribute to theorization in this area by articulating and illustrating a model of documentation (i.e., document creation) from the first-person perspective.

1.2 Models of documentation

To a small extent, previous literature in document theory has proposed models or frameworks for conceptualizing documentation, as reviewed by Lund (2009). Here I outline and assess three such conceptualizations, which frame the articulation of a first-person theory: that of that of Lund (2004), Gorichanaz and Latham (2016), and Gorichanaz (2016). The first of these seems to be the dominant model among scholars, as it is the most cited and represents a consensus view of scholars besides Lund, such as Buckland (2007) and Pédauque (2003).

1.2.1 Lund's "complementarity perspective"

Lund (2004) developed a theory of the document and documentation inspired by Niels Bohr's complementarity theory in physics. His complementary view of the document has three aspects: the material/technical, the mental/informational, and the social/communicative. Lund defines documentation as the process of creating a document, and asserts that the process unfolds in time and entails:

-

a human producer

-

a set of media instruments for producing

-

a mode of using these instruments

-

the resulting document

For Lund (2004), documentation is constrained and enabled by many factors, from socioeconomic pressures to individual whims. It is also historically situated; to give a germane example, certainly some of the materials used by a 16th-century Italian artist will differ from those used by a 21st-century American.

This model of documentation has proven useful for the analysis of the creation and circulation of many kinds of documents; Lund (2016), for instance, describes student projects that used it for such analyses. It has also invited critique, such as by Skare (2009).

While still accepting the usefulness of this model, I suggest that it falls short of being able to account for first-person phenomena. As a third-person account, the model ignores the experiential (what Lund would call "mental") quality of the documentation process itself. Moreover, the model does not address what leads to the document, such as where the materials and ideas come from.

1.2.2 Gorichanaz and Latham's "document phenomenology"

Latham and I sought to develop a framework for analyzing documents that does not ignore the mental aspect of the document, which has not been studied to the extent that the "social" and "physical" aspects have been. We developed an analytical framework for the phenomenology of the document, which involves both documental being and becoming (Gorichanaz & Latham, 2016). The latter is most relevant to the discussion at hand, as it essentially describes documentation.

According to our framework, a document is formed when a person and an object come together, along with the lifeworlds of each. In this merging, the object furnishes intrinsic information (physical properties, e.g., letterforms) and extrinsic information (attributed properties, e.g., reviews); the person furnishes abtrinsic information (properties related to their psycho-physiological state, e.g., hunger) and adtrinsic information (properties related to their past and social life, e.g., memories). These four sorts of information are processed by the person, cohering as documental meaning.

This framework goes some way in showing the experiential aspects of documentation. Just as described with Lund's (2004) model above, this model has been used with success in student work for document analysis, particularly in the analysis of the meaning of museum objects (K. F. Latham, personal communication, May 16, 2017; e.g., Munson, 2017). However, Lund has pointed out that several things are left out from this model (Lund, Gorichanaz, & Latham, 2016), such as the physical processes in documentation (Lund's media and mode). In a word, this model lacks time.

1.2.3 Gorichanaz's "experience of document work"

In another work, I sought to explore the lived experience of document work (more precisely, of documentation). I conducted a phenomenological case study with the head gardener at Shofuso Japanese House and Garden, a historic landscape site in Philadelphia, as she created a document: a comprehensive garden plan (Gorichanaz, 2016).

Through analyzing the case of this particular gardener, I developed an experiential framework of documentation that involves a foundation, process and challenges. "An underlying foundation supports the process of document work, and ...this process is marked by certain challenges" (Gorichanaz, 2016, p. 5). For the gardener working on this task, the foundational values included authenticity, education and reducing ambiguity; the technical process involved summoning diverse knowledge, channeling the master and stepping back; and the intermittent challenges were organizational and historical in nature.

This framework makes space for the experiential aspects of the process while also including the passage of time. However, it was developed inductively and was disconnected from other models of documentation, including those discussed above, as well as models of information behavior in the literature. It is also notable that this framework was developed on the basis of a single-case study and has not yet been further validated.

1.3 Modeling documentation in the first person

The frameworks surveyed above each have strengths and weaknesses relative to their capacity for modeling documentation in the first-person perspective. These strengths and weaknesses are summarized in Table 1. In this section, I synthesize these findings and present a new philosophical, descriptive theory of documentation. This is intended to be a first-person, time-sensitive framework that brings together the literature discussed here.

Table 1: Relative strengths and weaknesses of surveyed models on modeling self-portraiture

| Complementarity | Document Phenomenology | Experience of Document Work | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strengths | First model Time element | First-person perspective | First-person perspective Specific to document work |

| Weaknesses | No first-person perspective | No time element Not specific to making documents | Disconnected from other models Unvalidated |

Considered from the first person, a case of documentation is an experience. An experience is something identified as such and picked out from the flow of existence (Dewey, 1934). Thus the "something" in an experience can be conceptualized as the level of abstraction (Floridi, 2011) at hand, i.e., the set of phenomena of interest to a certain question. As Floridi (2011) describes, levels of abstraction are teleological; in this case, the purpose is narrative. What qualifies as an experience is always up to the experiencer; in the words of Heidegger (2010, p. 53), it is "in each case mine"; in those of James (1950, p. 222), it is "as owned." Dewey (1934) offers some guidelines for analyzing experiences, which have narrative completeness and include several dimensions: continuity between intra- and extra-experience aspects of existence; deepening complexity as time progresses; meaning that persists after the experience concludes; challenges encountered; and anticipation of culmination.

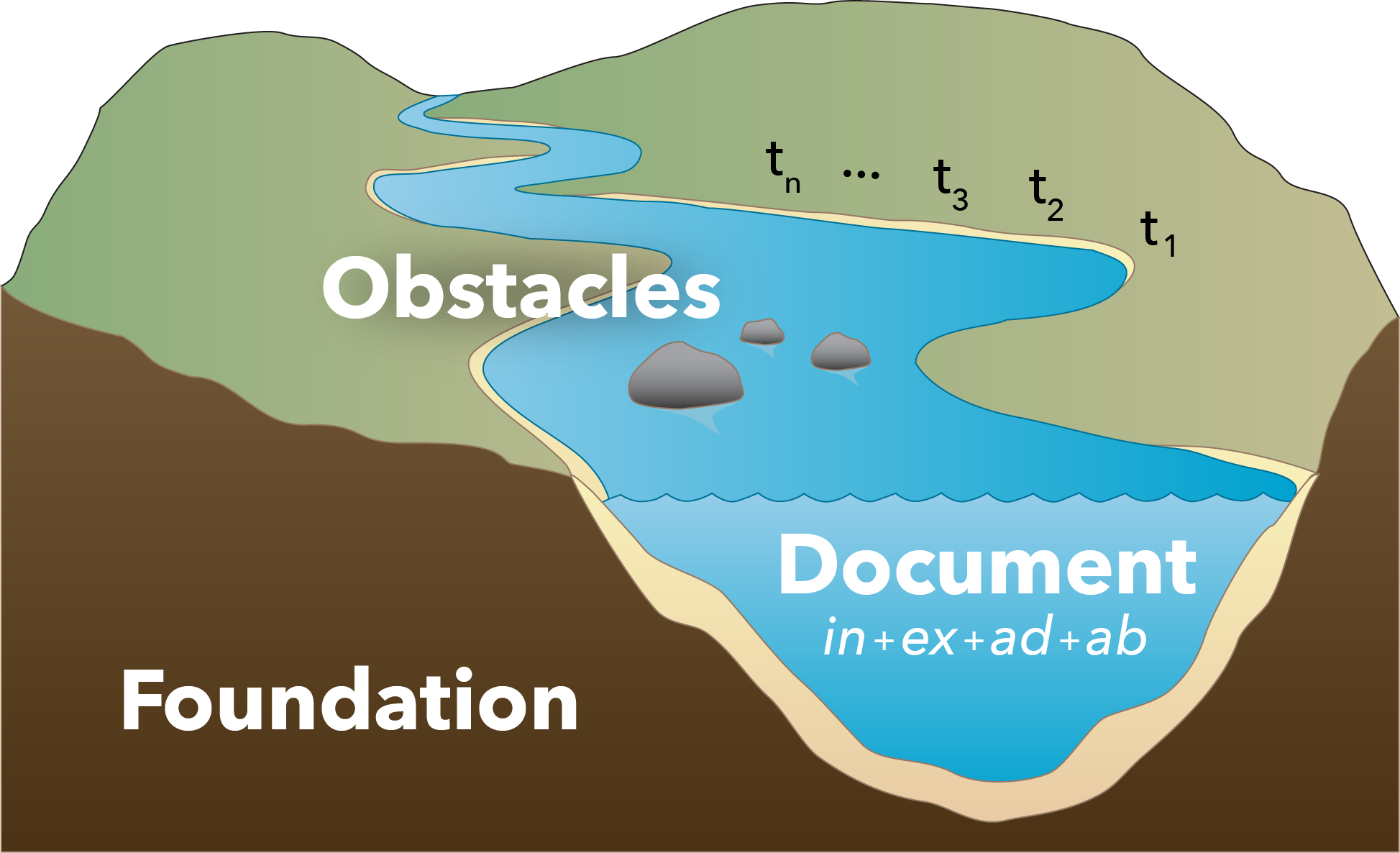

As Heraclitus famously observed, the flow of existence can be likened to a river: "You cannot step into the same river twice, as fresh water is always flowing around you" (frag. 12). Thus, an experience can be likened to a segment of a river. A river includes a riverbed, a flow of water and a number of obstacles (e.g., rocks, branches). This structure echoes the framework of foundation--process--challenges that I previously developed (Gorichanaz, 2016); that is, foundation corresponds to the riverbed, process to the water, and challenges to the obstacles. Building on this, the river metaphor serves as the basis for my framework of the experience of documentation, as pictured in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A synthesized, first-person model of documentation as a river

Water is the most salient aspect of the river, and so it is a good place to start. Water is analogous to process in Gorichanaz (2016), which includes the technical effectuations that are involved in document work. Implicit in this account is the document itself, which is being created through the process as time goes on. Thus, in the present framework, process is subsumed under the document itself. "The document" here is to be understood as described in the framework of document phenomenology (Gorichanaz & Latham, 2016), i.e., as a conglomeration of intrinsic, extrinsic, abtrinsic and adtrinsic information (in short: person+object). A caveat, however: the borders of the document while it is being made extend beyond what may be considered the document when it is finished; that is, the tools, medium and mode are also part of the document-in-progress. That assertion is supported by research in psychology which finds the distinction between subject and object to dissolve in the experience of art-making (Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Merleau-Ponty, 2012).

Following Heraclitus, we can imagine time to be represented by the movement from point to point along the path of a river. A case of documentation, then, is analogous to a certain number of points along the river. Of course, the river continues beyond the endpoints in both directions: the materials that gave rise to a document existed before the document was made, and they will still exist (in some form) after the document decays (pursuant to the first law of thermodynamics, i.e., that energy can neither be created nor destroyed). Thus a case of documentation can be analyzed at a number of times t appropriate to the case: t~1~, t~2~, t~2~, ..., t~n~. Depending on the starting point that is chosen, a case of documentation could be conceptualized to include information seeking and other parts of information behavior.

The riverbed (foundations) and obstacles (challenges) are adapted from the framework in Gorichanaz (2016). The riverbed corresponds to the path of the river—the guiding values, purpose and narrative structure of a case of documentation. The obstacles correspond to things that come up in the process that are experienced as objectively present (Heidegger, 2010, i.e., vorhanden, also translated as present-at-hand)—that is, as moments of breakdown rather than part of the flow of experience. The river, as the document, flows around these obstacles.

This framework of the experience of documentation seems to address the shortcomings of the previously-developed frameworks described above while bringing together their strengths. It offers a way to think about the development of a document over time (including the person, object, tools, setting, etc., as relevant to the given experience) in a way that honors the first-person experience thereof and tries to bring together previous literature.

2 Illustration: Self-portraiture as documentation

The model of documentation described in the previous section will now be illustrated in the analysis of specific examples of documentation—the work of visual artists as they create self-portraits. To situate this study, I will briefly review the literature on art and information behavior.

2.1 Art and information behavior

Art has seldom been considered in information science research. Even so, there has been some recent theoretical work establishing that art-making can be fruitfully understood as a form of documentation (Gorichanaz, 2017a; Kosciejew, 2017). To speak of empirical research, there has been some work exploring art as information and art-making as a matter of human information behavior/practice. Cobbledick (1996) was the first to do so, in an interview study of four faculty artists. Since her work, a number of other researchers have contributed; William Hemmig (2008) provides a review of this literature, drawing the following conclusions:

-

Artists seem to require information for five distinct purposes: inspiration, specific visual reference, technique, marketing and art world trends.

-

Artists frequently need information on subjects unrelated to art, so art libraries rarely serve them well.

-

Like information behavior in general, creative information behavior is idiosyncratic.

-

Artists have a strong preference for visual information.

As relevant to the discussion here, a notable contribution in the literature is that of Cowan (2004), who was the first to conceptualize artists' information seeking outside the library, in a hermeneutic-phenomenological case study. Cowan interviewed one practicing artist and uncovered five main sources of information in art-making: the natural environment, the work itself, relationships with one's own artwork and with other artists and works, self-inquiry, and attentiveness. A key observation Cowan makes is that the artist does not view her art-making as involving information seeking or needs; rather, it is a joyful process of dialogue and perception. Cowan remarks that the artist's "processes are fluid, interrelational, dynamic, and creative; they rely on the action of creating understanding, rather than finding pre-existing information" (2004, p. 19, emphasis hers). Cowan is one of the first information behavior researchers to point out "creating understanding" as an activity; this concept is explored further below.

In his review article, Hemmig (2008) remarks that there has been almost no study in information behavior of artists who were not also faculty or librarians. He then conducted such a study (Hemmig, 2009), which validated the findings he drew in 2008. After Hemmig, there have been a few studies of artists' information behavior. These include Mason and Robinson (2011) and Robinson (2014); both these studies further validated Hemmig's work.

To be sure, there has been some recent research on information seeking in artistic domains beyond visual fine arts (e.g., painting), including music (see Lavranos, Kostagiolas, Martzoukou, & Papadatos, 2015), theater (e.g., Olsson, 2010) and writing (see Desrochers & Pecoskie, 2015). Because the present study is focused on the information behavior of artists as it applies to self-portraiture, these contributions are not reviewed here. However, it is notable that, like the research on visual artists, these works also limit themselves to information seeking rather than creation and use. Additionally, there has been some research on information literacy instruction for art students; Greer (2015), for example, discusses some additional references outside the information science scholarly literature which corroborate the discussion here, though her chief aim is addressing information literacy issues.

Though this body of research offers a coherent view of artists' information behavior, it only addresses information needs and seeking, rather than use or creation. The lack of research on artists' information use is a crucial limitation in light of Cowan's (2004) finding that artists may not view themselves as information needers and seekers, but rather as understanding-creators.

Indeed, this critique can be levied against information behavior research in general (Case & Given, 2016; Fidel, 2012; Ford, 2015; Vakkari, 1997; Wilson, 1997). Based on this, there seems to be ample room for research on the creation and use components of the information--communication chain, and art is certainly a domain in which such research can be done.

To this end, an additional study emerges as relevant, which was not reviewed by Hemmig (2008) and appears to be disconnected from the rest of the literature discussed here. It is the unpublished doctoral dissertation of Tidline (2003), who conducted a narrative analysis of the information behavior of artists. Tidline found that artists see their chosen medium of expression as significant and that engaging with other artwork is an important part of the creative process and artists' development. Principally, Tidline sought to provide evidence for the informativeness of art. In light the work surveyed thus far, this proposition now seems to be secure. In her conclusion, Tidline called for further research on how artists work with information in art-making. To date, her call has not been answered.

2.2 Methodology and methods

To explore art-making as a form of documentation, I recruited visual artists from Philadelphia to create self-portraits and keep track of their process according to a research protocol and participate in a follow-up interview. Self-portraiture was chosen because it allowed for me to enroll artist participants who worked in a broad range of styles and media to all create work participating in the same genre—a balance of diversity along some dimensions and homogeneity along others. (Had I asked the artists to do a landscape, for instance, there may not have been any abstract expressionist participants.) This study sought to respond to the research question: What is the nature of the lived experience of self-portraiture as a kind of documentation?

Methodologically, this study used phenomenology of practice, the toolkit for conducting hermeneutic phenomenology developed by van Manen (1990); van Manen (2014). Phenomenology of practice employs the inductive, idiographic analysis of particular cases to describe and interpret the complexity of the lifeworlds of human actors and draw out findings that generate knowledge that is not merely gnostic (cognitive, procedural) in nature; rather, phenomenological knowledge is pathic (emotional, ontological) (van Manen, 2014) and poetic (a holistic, from-the-inside experience of reality) (Taylor, 1998). The study also draws from arts-informed research (Cole & Knowles, 2008; Savin-Baden & Wimpenny, 2014). Arts-informed research uses art-making as a way of understanding a broader set of issues of interest to a given academic discipline. It seeks to represent and advance knowledge in ways that may challenge traditional academic boundaries (Cole & Knowles, 2008). Though arts-informed research is new to information science, it is not without precedent Hartel (2014a). As Hartel and Savolainen (2016) note, arts-informed methods lend themselves to interpretative metatheories. Thus, I take arts-informed research to be compatible with phenomenology of practice.

To carry out this study, I recruited participants to create self-portraits. So that I could be as open as possible, I did not define self-portrait in my recruitment materials, nor did I stipulate a medium that the artist must use. I recruited my participants in the manner of convenience sampling.

I collected visual and verbal empirical material as the artists individually worked on their pieces. At the end of each art-making work session, the participant photographed their in-progress portrait as well as the tools they used, any sketches they made and material they referenced (such as stock imagery, other artists' works, and poetry). The participant then recorded their answers to a list of questions about their art-making session. These questions were designed to elicit details of the art-making session as lived and to surface tacit knowledge through questioning about temporary breakdowns and encouraging the use of metaphors.

Then, about a week after each piece was finished, I conducted a follow-up interview with each participant. This interview was semi-structured, and some of the questions depended on the particularities of each artist. The follow-up interviews ranged in duration from 22 minutes to 92 minutes (mean: 43 minutes). During the interview, I probed the participant's intentions, inspiration and process for details that did not emerge in their in-progress accounts. Where appropriate, I used images the participant provided throughout the process, and the finished portrait itself, to elicit richer responses during the interview, a technique recommended by Rose (2016). When possible, this interview took place where the portrait was created (see Figure 2. This way, the participant could show me how they used the space while creating the portrait. For the interviews that took place elsewhere (e.g., in a café), I asked that the self-portrait be present, and this enriched the interview. I took handwritten notes during each interview, and each participant allowed me to audio-record the interview. Immediately after each interview, I typed up my field notes and added additional comments that I did not have time to write in situ. Within a few days, I transcribed all the audio material.

Figure 2: The setting of Brian's interview, in his studio. His self-portrait sat between us, and we referred to it continually as we talked.

All the material from each individual constituted a phenomenological example (the methodologically preferred term for what might otherwise be called a case). Different examples comprised different numbers of art-making sessions. Analysis began along with collection and proceeded iteratively according to guidelines given by Smith, Flowers, and Larkin (2009) and van Manen (2014). A quantitative summary of the empirical material collected is given in Table 2.

Table 2: Quantitative summary of the empirical material collected with each artist participant.

| Artist | Medium | Sessions | Session Duration | Session Interview Length | Follow-up Interview Duration | Photos |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brian | Oil, mixed | 4 | 40 mins | 3 mins | 50 mins | 6 |

| Brianna | Acrylic | 4 | 4 hrs | 12 mins | 23 mins | 17 |

| Britt | Acrylic | 3 | 70 mins | 655 words | 22 mins | 17 |

| Emily | Oil, Polaroids | 11 | 40 mins | 300 words | 36 mins | 7 |

| Jeannie | Oil, mixed | 9 | n/a | 12 mins | 92 mins | 24 |

| Justin | Stained glass | 4 | 3 hrs | 7 mins | 42 mins | 39 |

| Tammy | Graphite | 2 | 2 hrs | 9 mins | 35 mins | 16 |

In my analysis, I sought to, first, identify the narrative, thematic structure underlying each participant's experience of self-portraiture and, second, illustrate and possibly extend the theory described in the previous section. My analytical strategies were informed by compatible, established guidelines for arts-related research (Savin-Baden & Wimpenny, 2014) and phenomenology of practice (van Manen, 1990; van Manen, 2014). Analysis involved multiple rounds of open coding. To begin, I coded for processes (actions), emotions (felt meanings) and descriptions (topics). I referred to the visual material as necessary to support my understanding of the verbal material. I repeated this 2--3 times for each example, coding snippets that I had missed or re-coding snippets in light of my shifting understanding; this iterative coding technique is known as the constant comparison method, and though it originated in grounded theory, it is now a cornerstone of qualitative analysis in general (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014, p. 285). I also created memos throughout my analysis, which included thoughts that emerged while I was actively analyzing as well as those that struck me while I was doing other things. Next I sought to develop a narrative description (Miles et al., 2014, pp. 91) or anecdote (van Manen, 2014, pp. 256--260) to express each example. Drawing from the coded snippets, I first listed each "story beat" (Coyne, 2015). This helped me see the role that the various aspects of the artist's account played in the creation of their self-portrait. Building on this list, I then crafted a narrative of about 1,000 words from the artist's point of view. As much as possible, I used the artist's own words, drawn from their session interviews and the follow-up interview. However, elements were reordered and edited for clarity. After a first draft of this narrative, I revisited the empirical material to see if anything was missing. I then revised the narrative as needed. In phenomenology of practice, such narratives are considered the main research product (van Manen, 2014, pp. 256--260); however, to aid in the communication of my findings and to more clearly contribute to the literature, I conducted additional analyses, which are described below.

Initially, each participant's experience was analyzed individually so that I could immerse myself fully in that individual example. Once all the examples were gathered and analyzed, they were compared and contrasted through iterative consideration of individuals and the group. This is the strategy employed in interpretative phenomenological analysis (Smith et al., 2009), which has been validated in information science (VanScoy & Evenstad, 2015); it is compatible with the principles of cross-case analysis described by Miles et al. (2014), and it makes sense in the context of my phenomenology-of-practice study as a way to expose the tension between the individual and the group, as counseled by van Manen (2014). Through this analysis, I was able to appreciate what made each case unique.

After this, I revisited the theoretical model of documentation that I discussed in the first part of this paper. I worked to determine whether the themes I discerned in this study corresponded to the aspects of that model (Foundation, Obstacles and Document), and whether any were unclassifiable. Last, I returned again to the original transcripts to see if I saw anything new that I had overlooked in my prior analyses. I did not directly employ the theory in writing the narratives or conducting the theme analysis. Still, its principles (e.g., that documentation is done with a purpose) were likely working in the background, as a hermeneutic lens. There is a danger with such a method: A pre-defined theory may impose undue assumptions on an analysis, such as creating blindspots or overemphasizing trivialities (Smith et al., 2009; van Manen, 2014). And while a Husserlian method would attempt to "bracket out" all understandings prior to an analysis, a Heideggerian method disputes the possibility of such a thing (van Manen, 2014); for van Manen (2014), a middle-ground solution is to articulate one's background and assumptions as much as possible.

To be sure, there are several different documents at play in this study: the self-portrait as a document, the artist's documentation of their creative process, the interviews I conducted, and perhaps others. Any of these documents could be analyzed as lived experience examples of documentation in their own right. And all of them could shed light on the analysis of any one of them. Thus it is important to not lose sight of the object under study, pursuant to the research question. In this study, the documentation in question was the creation of each self-portrait.

2.3 Findings

As described above, to understand the lived experience of art-making, and specifically self-portraiture, I engaged artists to create self-portraits and document their experiences. This work resulted in a narrative description of each participant's experience. These narratives can be found online at http://selfportraiture.info.

To help us better understand these results, we can consider the themes that can be found within and across these accounts, and how these relate to the model of documentation presented in the previous section. Thus, in this section, I present the results of a thematic analysis of the experiences. First, we will consider those themes shared among all the experiences, then those shared among most, and finally some themes that emerged only in two or three accounts but nonetheless are particularly intriguing. These themes are summarized in Table 3 and are described in the following paragraphs. Note that the table also includes mappings to the framework developed in the previous section; this is discussed after the themes, in Section 2.7.

Table 3: Summary of themes discerned in the artists' experiences. Letters in parentheses refer to Foundation, Document and Obstacles, which were presented in the previous section. In the case of D, the italicized letters refer to intrinsic, extrinsic, abtrinsic and adtrinsic information.

| All | Most | Few |

|---|---|---|

| Communicating (F) Memories (D ad) References (D ex/ad) Self-efficacy (D ab) Taking breaks (D ab) Stepping back (D ab) Tension/relaxation (D ab) | The hump (D ab/in) Mistakes (O) Non-decisions (D in/ab) Other people (D ex) Other works (D ex) Ti esti (F) | Deep knowledge (D ab) Finished? (D in) Money (O/D ad) Things just for me (D in) Thinking by sketching (D in) Thinking at work (D ex) |

2.4 Themes found in all the experiences

2.4.1 Communication

All seven partipants demonstrated a communicative intent, suggesting that communication is a Foundation of self-portraiture. For some, this surfaced as consciously trying to say something through their art. Brian, for example, described adding "referential marks to show more complete thoughts," some of which were "almost like written language but not quite, like those fuzzy memories that you can't quite make out." Beyond linguistic metaphors, Brianna described letting her body language express a felt meaning, and Jeannie sought to express the interplay between inside and outside in her sense of self through painting on the frame and depicting her brain and thoughts. Communicating in another sense, some of the participants sought to show their skill at their craft. Emily, for example, switched from photography to painting for her project in part because "I want my skills to come through, and my skills are in painting and not necessarily something new." Also, Justin mentioned that he wanted his stained glass piece to seem difficult even to other highly skilled glass artists. Finally, most of the artists posted photographs of their self-portraits on Instagram (often while in progress), making manifest this communicative intent. As part of communication, the artists described thinking about how viewers will see and interpret the piece, and the choices they made were strategic to this end.

2.4.2 Memories

Two other themes common to all the artists in my study were memories and reference materials. These are related in that they both constitute adtrinsic information in the experience of self-portraiture, and indeed sometimes they overlapped. Brian, for instance, explicitly considered his memories to be "internal references." Memories arose in two ways: during conscious self-reflection, in which memories were sought and conjured, often in a distinct stage of work; and spontaneously, intermingled in other stages.

2.4.3 Reference materials

In terms of external reference materials, most of the artists used photographs, some used sketches, some used the work of other artists, and some used the work itself as a reference. To give some examples of the last of these, Emily produced an all-blue photo by accident and then used that color blue as the background in her painting, and Tammy took photos of her drawing at each stopping point, and she often referred to these photos as evidence of previous states of the work to remind herself of how things were before she fixed them (or, sometimes, accidentally made them worse). Reference materials were used in two ways: first, directly, in that the artist attempted to duplicate some aspects of the reference; and second, indirectly, in that the artist immersed themselves in the reference to get a general sense impression and then freely worked on the sketches. For an example of the latter, Jeannie referred to a book for inspiration for her farm machinery, "just to have a general feeling" of a "mechanistic impression." The artists only used their reference materials up to a point; sketches guided the process in the beginning, and other references were used through the middle stages, but by the final stages all reference materials had been abandoned in all cases. As Brianna said, "I don't worry about matching the photograph anymore—I just want to do what will look good in the painting." At this point, the work itself becomes the artist's key reference.

2.4.4 Self-efficacy

Another important theme in these experiences was self-efficacy. Some of the artists sought to ensure self-efficacy by choosing a project they knew they could do well, while others gained self-efficacy by succeeding at a dubious challenge. An exemplar of the former was Britt, who used her tried-and-true methods to paint comfortably, and an exemplar of the latter was Tammy, who did not do her self-portrait in her usual style, but all the same she finished the project proud of her success in drawing a face and eager to do another. Most of the artists fell somewhere between these extremes. For example, Brianna found some aspects of her painting to be very challenging, such as rendering her studded belt. All the same, on a day when she was having a difficult time at school and work, was relieved to come back to her self-portrait in the evening "because this is something I can do." All of the artists described feeling proud and accomplished after finishing their pieces.

2.4.5 Taking breaks and stepping back

Much like research papers and dissertations, the self-portraits in this study were not made in one, nose-to-the-grindstone session. On the contrary, all of the artists described taking breaks, from minutes to weeks, and while they were working, stepping back. Both of these seem to be methods of gaining a refreshed perspective on the piece. As Emily described, "When I take breaks and then come back, I have completely fresh eyes on the painting. When I work for long periods of time, I end up making more mistakes and redoing a lot of that work." Regarding stepping back, most of the artists physically did this. Tammy, in addition to physically stepping back, took photos of her drawing with her smartphone and then inspected the image on her phone, which helped her see things that needed to be fixed that were not apparent by just looking at the drawing.

2.4.6 Tension and relaxation

The final theme observed in all the participants' experiences included the opposing feelings of tension and relaxation. For these artists, working on art is, by and large, a relaxing activity. This was often described in contrast to the hectic nature of the rest of life. Even so, certain tensions came up in the process. Sometimes, interestingly, these were only noticed when there was a pause in the process. For example, Brianna and Emily described only noticing their lower back pain when they took a break. In other cases, tension was experienced in a more visceral way, perhaps as a reaction to some difficult point in their work. Justin, for example, described the tension he felt while his glass paintings were firing—a high-risk time in the process.

2.5 Themes found in most of the experiences

2.5.1 The hump

A key point in the dissolution of tension was getting over "the hump" of the process. All the artists except Brianna and Tammy described working faster as the piece neared completion. Most of them described the turning point through the metaphor of climbing a hill. In Emily's words, the "hump" is "a period of frustration before I can coast, when I don't like how it looks." Jeannie refers to it as a "plateau," a brief landing during a climb that affords clarity on the journey. As she describes in one of her session interviews:

I've kind of reached this little plateau. But it was hard to push myself up to this point. But what's good about the plateau is you have a bit of a view of how things are, and then you could even see the top. Now my vision of what the whole piece will look like is much clearer.

2.5.2 Non-decisions

The artist's experiences show many decisions being consciously made in the creation of their works. However, sometimes what an onlooker might want to call "a decision" was in fact not consciously decided by the artist. I call these non-decisions, because there was no deliberation and no choice was made; rather, the result sprang seemingly from nowhere. Perhaps a decision was made subconsciously, but in the artist's experience it did not register as a choice. For example, Jeannie knew from the start that her self-portrait would be square. She did not first consider a number of aspect ratios and then make the decision to do a square self-portrait; rather, squareness was always a part of her vision of this self-portrait. To give another example, Tammy never consciously decided to create a head portrait (i.e., a portrait where only the person's head is shown). In our follow-up interview, when I mentioned that another artist (Brianna) had done a whole-length portrait, Tammy remarked that she had never even considered not doing a head. Non-decisions were found in all but Brian's, Emily's and Justin's narratives. What is a non-decision for one artist may be a decision for another artist. While Jeannie's self-portrait was going to be a square from the start, Justin spent months ideating his portrait's format. And whereas Tammy "non-decided" to do a head, Emily wrestled over what about herself she would depict, and how.

2.5.3 Other people and works

Most of the participants, at one point or another, involved other people in their process of self-portraiture. Only Brian and Tammy seemed to really do their pieces alone. Justin, for instance, mentioned soliciting feedback as he was trying to capture his likeness in his painting: "I ask my son and my wife, and they say, 'No, that's not the right one.' ... Anyone who comes to visit my studio, I ask for feedback." Jeannie found inspiration for elements of her piece from her sister and a discussion group. Emily went so far as to include photographs of other people in her self-portrait. In addition to other people, most of the experiences in this study also involved other works. Brian, for example, worked on other pieces in breaks while his self-portrait was drying. Jeannie, similarly, works on several pieces at once and described how the colors she mixes for one painting sometimes end up being the colors she uses for other paintings. Tammy used other works as a way to ideate her self-portrait; she began by doing what she called "flow pieces," where she freely and meditatively pushed around and applied paint, somewhat akin to the way an athlete does warmups prior to competition.

2.5.4 Mistakes

Above we have seen examples of themes that fall under Foundations and Document in my model of documentation. An example of Obstacles is the theme of mistakes. All the artists in my study except Brian described mistakes they made. Often these mistakes were sources of tension, another theme. Britt, for example, moved her projector between sessions and had a hard time lining it back up. Britt, Emily and Tammy met difficulties in rendering the proportions: first one feature is too big, and then another. Jeannie, ever conscious of the dangers of applying too much paint, finds herself doing just that. For most of a piece's development, the artist fixes these mistakes. However, what I found interesting is that eventually, mistakes are embraced. Either it's too late or too much trouble to fix them, or they produce an interesting effect. As Brianna said, "And when I think I'm done, I realize [the hands] are way too big. It bothers me, but at the same time I like the distortion," and afterwards she does not change them (see Figure 3). Emily was inspired by the embraced accidents of masters such as Cézanne, and she found herself doing the same in her work. As she said, "Those accidents are the fun part, after all. It's completely unintentional, but it's intentional that I leave it."

Figure 3: Detail of Brianna's portrait after her second session. She is reworking the hands, which will end up "too big."

2.5.5 Ti esti

In philosophy, the ti esti question is that of what it is to be something. Four of the participants posed such questions while doing their self-portraits, generally at the beginning. Some considered what a self-portrait is. Brian, for instance, said that he considered all his work to be self-portraits, and he deliberated on what would make this piece different. All four of these artists raised the question of the self. To quote Jeannie: "I am so much—I don't even know what's down deep." The answers to these questions guided the process, and therefore the ti esti theme belongs to the Foundation of this form of documentation. Put differently, the artists considered not only what they were as selves, but how to depict themselves as selves. In our follow-up interview, Brian described this as collapsing his life into a single image:

All the things I try to collapse into this one thing are probably all the things I find too difficult to the take time to explain to somebody...A painting, to me, is all that collapsed nature, because I probably will never sit with the viewer, and it would be so narcissistic for me to be like, "Let me start at the beginning, and I'll roll you through the last 27 years of my life."

Jeannie's example offers further detail. "So much of my existence is on the border," she said at the beginning of her process. "I can't even identify myself without thinking about the interface between inside and outside." Consequently, she played with this interface in her composition and content.

This brings up another mode of self-representation: Several of the artists described not only wanting their image to resemble them, but wanting the artifact to look like it was made by them, i.e. manifesting their style. Justin was particularly vocal on this point. "I wanted a certain look to it," he said. "I wanted it to be kaleidoscopic, colorful, psychedelic—and those characteristics I like to keep in all my art." Along with memories and self-efficacy, two themes described above, the self was a continual topic of reflection for those participants who engaged in the ti esti question. In some cases, doing the self-portrait seemed to influence the self-concept. Justin, for example, said, "Both the trip [to Colorado] and this project have already been pivotal in the way I see myself." Thus not only can the self-portrait reflect the self, but it can also help constitute it.

2.6 Themes found in a few of the experiences

In addition to those themes found in all or most of the artists' experiences, it is worth spending a few moments on themes that arose in only two or three of the artists' experiences but are nonetheless intriguing. Some may be good candidates for further research.

Figure 5: "Just for me" magical symbols in Justin's self-portrait

- Deep knowledge

-

Brianna and Emily described moments where they tapped into deep knowledge of human anatomy in order to render something how it should be without referring to or in spite of their photographic reference.

- Just for me

-

Though all the artists demonstrated that their work was communicative, Brian and Justin mentioned putting secret elements in their self-portraits that were just for them (see Figure 5).

- Money

-

Brianna and Emily mentioned money as a constraining factor in their work. For Brianna, this meant dealing with subpar brushes in exchange for good paint. For Emily, this meant abandoning film and going to painting.

- Thinking through sketching

-

Brianna, Jeannie and Justin used sketching as a means of working out aspects of their self-portrait, such as composition.

- Thinking while at work

-

Even while they were not physically and consciously doing their self-portraits, Britt and Emily found themselves thinking about their self-portraits while at work. Similarly, Tammy mentioned thinking about hers while at the store.

- Unsure if it's done

-

Some of the artists seemed to know when their piece was finished. Brianna and Jeannie, however, said that they thought it was done but it might not be, and that they may do a bit more work.

2.7 Relating the themes to the theoretical model

In Section 1.3 I developed a descriptive theory for analyzing experiences of documentation, including art-making and self-portraiture. As discussed, I did not directly employ this model in writing the narratives or identifying the themes discussed above, though it surely contributed to my hermeneutic lens as I was working.

To test the theory, I considered whether the themes I identified in this study could map onto the various concepts in the model. These mappings are shown in Table 3. To begin with Foundations, I determined that the themes of communicating (anticipating the audience) and ti esti (questioning self and genre) were relevant. As for Document, I found the majority of the themes to belong this category; within Document, most of the themes related to abtrinsic information—that is, feelings and other psycho-physiological states—including self-efficacy, taking breaks, stepping back, and tension and relaxation. This seems reasonable, given that the focus here was on the individual's lived experience, and much of the empirical material was introspective. To be sure, though, among the themes found in all or most of the experiences, there were examples of intrinsic, extrinsic, abtrinsic and adtrinsic information. Finally, for Obstacles, the theme of mistakes was found in most of the experiences, and the theme of money was found in a few. It is notable that mistakes were not always perceived to be negative (as discussed above), as the word obstacle seems to imply, but rather something to be embraced.

All in all, there were no themes that could not be mapped onto the model, and no concepts in the model were unmapped. This seems to lend at least provisional support to its validity and usefulness, though of course this question can be taken up with more systematicity and detail in future research.

3 Discussion

In this paper, I have presented a new theoretical model to describe documentation from the first-person perspective, and I have applied the model in a study of visual art-making qua documentation.

To be sure, other fields have explored the creative process to some extent. Art historians, conservators and curators, for instance, have made use of interviewing and document analysis techniques to understand how particular artworks came to be and what to do with them (Hummelen & Sillé, 1999), and literary scholars have used drafts, correspondence and others documents in genetic criticism (Deppman, Ferrer, & Groder, 2004). The present study has sought to show the relevance of these methods and interests to information science, inviting future work at the intersection of these various fields. This is in the spirit of arts-related research, which, as mentioned above, seeks to challenge traditional academic boundaries.

However, it should be noted that phenomenological research has different concerns than the above-mentioned areas of inquiry, though there may be some overlap. Other methods may be concerned with issues of conservation, historical fact or psychology; but phenomenological research is concerned with felt meanings and the lifeworld (van Manen, 2018). This is the crux of what is at issue in the question of the first-person perspective.

3.1 Information in the first person

The first-person perspective is not totally alien to information science; arguably, the constructivist and cognitivist paradigms were first-person ones. Those paradigms have their shortcomings, and in many research areas they have fallen out of favor (see Talja, Tuominen, & Savolainen, 2005). In this paper, I have put forth a first-person model of documentation that attempts to overcome those shortcomings by taking a phenomenological perspective. This work seeks to contribute to ongoing conversations in information experience (Bruce et al., 2014) and document experience (Latham, 2012; Latham, 2014).

I contend that the findings this study has generated could not have been generated outside the first person. The power of this approach can be seen most clearly in Justin's experience: His trip to Colorado gave him a deep and energizing self-confidence, and after returning home he brought himself to his project differently. Justin maintains that the trip and this shift in mindset were critical in his completion of the project, and yet this is not visible from the outside.

But what use is the first person? To give one example, knowing the potential obstacles in a given domain or activity can allow information professionals to anticipate people's information needs as well as the nature of information sources that may be helpful in dealing with those obstacles. Essentially, information professionals can serve their constituents better by putting themselves in their constituents' shoes, and first-person models can help information professionals to do that. I see the first-person perspective to be supplementary, rather than antagonistic, to the third-person perspectives offered by metatheories such as sociocognitivism. As such, the findings from my study should be understood as enriching, rather than dichotomizing.

3.2 Temporality and document experience

Next, this study sought to lend some insight to the temporal aspects of documentation. Unlike a baseline-format image on a slow internet connection rendering one line at a time, we have seen that the creation of a self-portrait is not a straightforward, linear matter. The time of documentation is richly textured. My findings offer some concepts for understanding the creation of a document as part of the flow of time: taking breaks, stepping back, tension and relaxation, the hump, and handling mistakes.

The different themes I discerned manifest differently at different times t of the documentation process, and some appear only at certain stages. For example, mistakes early on are often corrected, but mistakes later on are embraced; and reference materials are used early on but not later in the work.

Of course, it is an open question as to which, if any, of these concepts apply to documentation experiences outside self-portraiture or even art-making. This is a limitation of the present study's focus on self-portraiture. Further research will be able to clarify the extent to which these findings are relevant to self-portraiture, to art in general, or to documentation in general, etc. Preliminarily it is worth noting, however, that in my earlier study of documentation at a Japanese garden (Gorichanaz, 2016), I discovered stepping back to be an important part of the gardener's process. Moreover, taking breaks and stepping back seem to be crucial parts of writing research.

Another area that may warrant further research is how a person's sense of speed and ease change over the course of a case of documentation. As described in Section 2.5.1, most of my participants experienced a "hump" in their process, before which work was slow, deliberate and sometimes difficult, and after which work was fast and generally easy. In my general model, this change is not conveyed (i.e., the river's width, gradient, turbulence, etc., are unspecified). It may or may not be the case that it should be.

3.3 Artists' information behavior

As discussed above, most of the information behavior research on artists has dealt only with information seeking. As Case and Given (2016) show, this is the case with information behavior research in general. To be sure, the information professions have long been interested in ensuring access to information, and information seeking is closely tied to access; however, information providers should also take into account what is to be done with the information that is sought, for when people judge relevance they do so with respect to a task at hand (Hjørland, 2010). Thus, information behavior scholars should account for other aspects of the information--communication chain.

In the domain of art, information behavior studies by Cowan (2004) and Tidline (2003) have done this, exploring the whole process of art-making in one particular project. The findings from those studies and mine are consistent. First, the artists in my study did not look at information seeking as a problem to be overcome or a gap to be leapt; it was, rather, a process of discovery, an exciting challenge—a search for inspiration rather than a solution. By now numerous researchers have pointed out that information behavior extends well beyond problematic situations (Kari & Hartel, 2007; Talja & Nyce, 2015), and my study further secures art as a domain in which this is the case.

My findings also add further color to the field's knowledge of the information behavior of artists at work, regarding, for instance, when reference materials are sought and used, and when they are abandoned. To this end, my study sheds light on the multifarious nature of information needs among artists; some people at some times seek representative references that will more or less be duplicated, some seek general impressions, and some seek broadly-defined ideas.

How can those who serve artists informationally, such as art librarians, put these findings to use? My study has shown how many different sorts of information bear on the understandings built in art-making, beyond those traditionally managed by information professionals. These include memories, feelings and impressions. Perhaps, then, a librarian could guide an artist through some of these possible forms of information in a reference interview, which may lead to the recommendation of other helpful information in the library's collection. Moreover, this finding offers some guidance for information literacy education for artists. My study showed how an artist's documenting their own process can help in this regard. For instance, Jeannie mentioned this project helped her think more consciously about the reference material she was using, which improved her process. Brian likewise felt that his work was honed because the self-interviews helped him better see what he was doing. Information literacy educators might recommend a similar strategy, perhaps utilizing a self-interview technique akin to what I used in my study, to help artists surface their own information behavior for themselves.

We can also consider how these findings shed light on the work of non-artists. Becker (1982) suggested that art is simply the kind of work that some people do—no inscrutable or divine genius here. So what if we looked to the work of artists to draw lessons for others? March (1970) did just this, calling social scientists to infuse their work with artistry by paying attention to aesthetic excitement, creative imagination and unanticipated discovery. He recommends techniques such as throwing all your notes in the air and seeing what new connections or ideas emerge from regarding them out of order. More recently, Clarke (2018) has argued that librarianship is a field of design (rather than social science), explicitly foregrounding the creative problem-solving involved in librarians' work. Following her argument, there is certainly something to be learned from the work of artists for information practice. Kohashi (2018) would agree; she recently gave a talk on the teleological similarities between book artists and librarians: both create points of entry, provide tools for understanding and inspire further inquiry. The artists in my study did their thinking through working, learned to listen to their mistakes, used their whole bodies in their work, practiced self-efficacy, took breaks and more. It would seem that even non-artists could use these techniques to bring a fresh approach to their work.

Conclusion

As novel documentary forms proliferate and our society becomes more visual, we must better understand non-textual documentary forms. One crucial element of understanding these forms is understanding the experience of their creation. This paper has engaged with the conceptual and metatheoretical foundations of information science and documentation with the aim of contributing toward that understanding.

This paper has provided a theoretical model for analyzing experiences of documentation. The model has three major elements—Foundation, Document and Obstacles—which characterize the experience of creating a document in space and time. It illustrated this model in an empirical study, thereby also furnishing thematic results about the artistic experience. In this study, the experiences of seven local artists creating their self-portraits were analyzed thematically. These themes express the nature of the experience of self-portraiture, but further research is needed to determine which of these themes may apply to other forms of art-making and documentation.

References

Bawden, D. (2007). Organised complexity, meaning and understanding. Aslib Proceedings, 59(4/5), 307--327.

Becker, H. (1982). Art worlds. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Briet, S. (2006). What is documentation? In R. E. Day, L. Martinet, & H. G. B. Anghelescu (Eds.), What is documentation? English translation of the classic French text (pp. 9--46). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Bruce, C., Davis, K., Hughes, H., Partridge, H., & Stoodley, I. (Eds.). (2014). Information experience: approaches to theory and practice (library and information science, vol. 9). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Buckland, M. K. (2007). Northern light: Fresh insights into enduring concerns. In R. Skare, N. W. Lund, & A. Vårheim (Eds.), A document (re)turn: Contributions from a research field in transition (pp. 316--322). Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang.

Case, D. O., & Given, L. G. (2016). Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking, needs and behavior (4th ed.). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Clarke, R. I. (2018). Toward a design epistemology for librarianship. The Library Quarterly, 88(1), 41--59.

Cobbledick, S. (1996). The information-seeking behavior of artists: Exploratory interviews. The Library Quarterly, 66(4), 343--372.

Cole, A. L., & Knowles, J. G. (2008). Arts-informed research. In J. G. Knowles & A. L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 55--71). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cowan, S. (2004). Informing visual poetry: Information needs and sources. Art Documentation, 23(2), 14--20.

Coyne, S. (2015). The units of story: The beat. Story Grid. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from https://storygrid.com/the-beat/

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Beyond boredom and anxiety: Experiencing flow in work and play (25th anniversary ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Day, R. E. (2014). Indexing it all: The subject in the age of documentation, information, and data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Deppman, J., Ferrer, D., & Groder, M. (2004). Genetic criticism: Texts and avant-textes. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Desrochers, N., & Pecoskie, J. (2015). Studying a boundary-defying group: An analytical review of the literature surrounding the information habits of writers. Library & Information Science Research, 37(4), 311--322.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Elgin, C. Z. (2017). True enough. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Fidel, R. E. (2012). Human information interaction: An ecological approach to information behavior. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Floridi, L. (2011). The philosophy of information. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ford, N. (2015). Introduction to information behaviour. London, UK: Facet.

Gorichanaz, T. (2016). A gardener's experience of document work in a historical landscape site. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 53(1). doi: 10.1002/pra2.2016.14505301067

Gorichanaz, T. (2017a). Applied epistemology and understanding in information studies. Art Documentation, 36(2), 191--203.

Gorichanaz, T. (2017b). Understanding art-making as documentation. Information Research, 22(4), paper 776.

Gorichanaz, T., & Latham, K. F. (2016). Document phenomenology. Journal of Documentation, 72(6), 1114--1133.

Greer, K. (2015). Connecting inspiration with information: Studio art students and information literacy instruction. Communications in Information Literacy, 9(1), 83--94.

Hartel, J. (2014a). An arts-informed study of information using the draw-and-write technique. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 65(7), 1349--1367.

Hartel, J. (2014b). An interdisciplinary platform for information behavior research in the liberal arts hobby. Journal of Documentation, 70(5), 945--962.

Hartel, J., & Savolainen, R. (2016). Pictorial metaphors for information. Journal of Documentation, 72(5), 794--812.

Heidegger, M. (2010). Being and time. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Hemmig, W. (2008). The information-seeking behavior of visual artists: A literature review. Journal of Documentation, 64(3), 343--362.

Hemmig, W. (2009). An empirical study of the information-seeking behavior of practicing visual artists. Journal of Documentation, 65(4), 682--703.

Hepworth, M., Grunewald, P., & Walton, G. (2014). Research and practice: A critical reflection on approaches that underpin research into people's information behaviour. Journal of Documentation, 70(6), 1039--1053.

Hjørland, B. (2010). The foundation of the concept of relevance. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(2), 217--237.

Hummelen, I., & Sillé, D. (Eds.). (1999). Modern art: Who cares? Amsterdam, Netherlands: Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage.

Jackson, F. (1982). Epiphenomenal qualia. The Philosophical Quarterly, 32(127), 127--136.

Jacob, E. K., & Shaw, D. (1998). Sociocognitive perspectives on representation. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 33(1), 131--185.

James, W. (1950). The principles of psychology, volume 1 (reprint ed.). New York, NY: Dover.

James, W. (2002). The varieties of religious experience: A study in human nature (centenary ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Kallinikos, J. (2009). Reopening the black box of technology artifacts and human agency. In F. Miralles & J. Valor (Eds.), Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2002), Barcelona, Spain, 15--18 December 2002 (pp. 457--464). Red Hook, NY: Curran Associates. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/190/1/Kallinikos-ICIS.pdf

Kari, J., & Hartel, J. (2007). Information and higher things in life: Addressing the pleasurable and the profound in information science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(8), 1131--1147.

Kierkegaard, S. (2009). Concluding unscientific postscript. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kohashi, A. (2018, January). Blurring the line between book artist and librarian: Special collections instruction as artistic practice. Paper presented at the College Book Arts Association Conference, Philadelphia, PA.

Kosciejew, M. (2017). Documenting and materialising art: Conceptual approaches of documentation for the materialisation of art information. Artnodes, 19, 65--73.

Latham, K. F. (2012). Museum object as document. Journal of Documentation, 68(1), 45--71.

Latham, K. F. (2014). Experiencing documents. Journal of Documentation, 70(4), 544--561.

Lavranos, C., Kostagiolas, P. A., Martzoukou, K., & Papadatos, J. (2015). Music information seeking behaviour as motivator for musical creativity: Conceptual analysis and literature review. Journal of Documentation, 71(5), 1070--1093.

Lund, N. W. (2004). Documentation in a complementary perspective. In R. W. Boyd (Ed.), Aware and responsible: Papers of the nordic-international colloquium on social and cultural awareness and responsibility in library, information and documentation studies (SCAR-LID) (pp. 93--102). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Lund, N. W. (2009). Document theory. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 43(1), 399--432.

Lund, N. W. (2016). How it all started: 1996, the first year of Dokvit. Proceedings from the Document Academy, 3(1), 2. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/docam/vol3/iss1/2/

Lund, N. W., Gorichanaz, T., & Latham, K. F. (2016). A discussion on document conceptualization. Proceedings from the Document Academy, 3(2), 1. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/docam/vol3/iss2/1/

March, J. G. (1970). Making artists out of pedants. In R. Stogdill (Ed.), The process of model-building in the behavioral sciences (pp. 54--75). New York, NY: Norton.

Mason, H., & Robinson, L. (2011). The information-related behaviour of emerging artists and designers. Journal of Documentation, 67(1), 159--180.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2012). Phenomenology of perception. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Munson, S. N. (2017). The spider: Anaylsis of an automaton. Proceedings from the Document Academy, 4(2), 1. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/docam/vol4/iss2/1/

Nagel, T. (1974). What is it like to be a bat? The Philosophical Review, 83(4), 435--450.

Ocepek, M. G. (2018). Bringing out the everyday in everyday information behavior. Journal of Documentation, 74(2), 398--411.

Olsson, M. R. (2010). All the world's a stage—The information practices and sense-making of theatre professionals. Libri, 60(3), 241--251.

Pédauque, R. T. (2003). Document: Forme, signe et médium, les re-formulations du numérique. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from https://archivesic.ccsd.cnrs.fr/sic_00000511

Robinson, S. M. (2014). From hieroglyphs to hashtags: The information-seeking behaviors of contemporary Egyptian artists. Art Documentation, 33(1), 107--118.

Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials (4th ed.). London, UK: Sage.

Savin-Baden, M., & Wimpenny, K. (2014). A practical guide to arts-related research. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense.

Skare, R. (2009). Complementarity -- a concept for document analysis? Journal of Documentation, 65(5), 834--840.

Smith, J., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, research. London, UK: Sage.

Talja, S., & Nyce, J. M. (2015). The problem with problematic situations: Differences between practices, tasks, and situations as units of analysis. Library & Information Science Research, 37, 61--67.

Talja, S., Tuominen, K., & Savolainen, R. (2005). "Isms" in information science: Constructivism, collectivism and constructionism. Journal of Documentation, 61(1), 79--101.

Taylor, J. S. (1998). Poetic knowledge: The recovery of education. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Tidline, T. J. (2003). Making sense of art as information (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Tkach, D. (2017). The situatedness of the seeker: Toward a Heideggerian understanding of information seeking. Canadian Journal of Academic Librarianship, 2(1), 27--41.

Vakkari, P. (1997). Information seeking in context: A challenging metatheory. In P. Vakkari, R. Savolainen, & B. Dervin (Eds.), Information seeking in context: proceedings of an international conference on research in information needs, seeking and use in different contexts (pp. 451--464). London: Taylor Graham.

Van Fraassen, B. (2008). Scientific representation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany: State University of New York Press.

van Manen, M. (2014). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

van Manen, M. (2018). Rebuttal rejoinder: Present ipa for what it is—interpretative psychological analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 28(12), 1959-1968. doi: 10.1177/1049732318795474

VanScoy, A., & Evenstad, S. B. (2015). Interpretative phenomenological analysis for LIS research. Journal of Documentation, 71(2), 338--357.

Wiener, N. (1954). The human use of human beings: Cybernetics and society. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Wilson, T. D. (1997). Information behavior: An interdisciplinary perspective. Information Processing and Management, 33(4), 551--572.

Worth, S. (2008). Story-telling and narrative knowing. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 42(3), 42--55.