Gorichanaz, T., and Latham, K. F. (2016). Document phenomenology: A framework for holistic analysis. Journal of Documentation, 72(6), 1114--1133.

Abstract. Purpose: This paper seeks to advance document ontology and epistemology by proposing a framework for analyzing documents from multiple perspectives of research and practice. Design/methodology/approach: Understanding is positioned as an epistemic aim of documents, which can be approached through phenomenology. A phenomenological framework for document analysis is articulated. Key concepts in this framework are include intrinsic information, extrinsic information, abtrinsic information, and adtrinsic information. Information and meaning are distinguished. Finally, documents are positioned as part of a structural framework, which includes individual documents, parts of documents (docemes and docs), and systems of documents. Research limitations/implications: Scholarship is extended with an eye toward holism; still, it is possible that important aspects of documents are overlooked. This framework serves as a stepping-stone along the continual refinement of methods for understanding documents. Practical implications: Both scholars and practitioners can consider documents through this framework. This will lead to further co-understanding and collaboration, as well as better education and a deeper understanding of all manner of document experiences. Originality/value: This paper fills a need for a common way to conceptualise documents that respects the numerous ways in which documents exist and are used and examined. Such coherence is vital for the advancement of document scholarship and the promotion of document literacy in society, which is becoming increasingly important.

Life is as infinitely great and profound as the immensity of the stars above us. One can only look at it through the narrow keyhole of one's own personal experience. But through it one perceives more than one can see. So above all one must keep the keyhole clean. ---Franz Kafka (Janouch, 1971, p. 191)

Do documents exist? Or, perhaps more to the point: How do documents exist?

Questions about existence are, of course, not unique to documents, as evidenced by the sprawling literature in ontological philosophy. Yet, as Heidegger (1927/2010) pointed out, most of this inquiry assumes existence as a fait accompli and is more interested in questions regarding, for instance, classification. In Heidegger's terms, traditional ontology asks questions about beings, not about being.

With documents, assuming existence as self-evident---failing to ask about being---raises a host of issues. If a document is taken to be anything that furnishes evidence or proof of something (Buckland, 1997), how is it that objects become documents? And why do some things become documents while others do not? How can we account for, to give Meyriat's (1981) example, Napoleon's letters, which furnished one sort of proof in the days of their progenitor but today furnish a different one altogether? Academic interest in documents has mostly sidestepped these questions, but the emerging neo-documentalist tradition (see Lund and Buckland, 2009) offers the opportunity to explore documental being and becoming.

As reviewed by Lund (2009), document scholars historically focused on the material aspects of documents; more recently, the academic focus has turned toward the social and perceptual aspects of documents. In this latter vein it is, by now, well accepted that documents only exist in the presence of a human actor. For instance, Meyriat (1981) described the document as:

...not inherent, but rather the product of will, either to inform or to be informed---the second, at least, being always necessary. If this will doesn\'t garner a response from the beholder, the information remains only potential. The object on which the information is written or inscribed is not yet a document. It becomes one when a question is asked of it and its information is activated. (p. 54, translation ours)

This leads us to conclude that all documents are ultimately idiosyncratic and context-bound, unique to each individual beholder and moment (Gorichanaz, 2015). In this sense, documents can be understood as affordances (Gibson, 1979/1986)---perceived possibilities---as they arise perceptually in the context of a particular person, object and environment. And yet, clearly there is something physical that exists in our library vaults and on our hard drives even when nobody is around to afford a document. What are these things, if not documents?

Confronting this apparent paradox, Lund (2009) asserted that all documents have three aspects---physical, mental and social---that exist complementarily. Skare (2009) demonstrated the feasibility of this framework so long as the three "complementary" aspects of a document are considered to be manifest simultaneously. In a similar vein, O'Connor, Kearns and Anderson (2008) presented a conceptualization of the document as a system of physical structure (corresponding to Lund's physical) and behavioral function (Lund's social), which is given meaning by humans (Lund's mental). However, open questions remain: for instance, how can the mental aspect be analysed? Thus far, the literature in document theory has focused on the physical and social aspects of documents and lacks deep consideration of the active role of the human involved (Buckland, 2015). Document studies is in need of a coherent body of literature that examines "the individual's mental relationship with documents" (Buckland, 2015, preprint p. 8). Latham (2012, 2014) also notes the missing individual in document studies and presented a route to bridge the gap through phenomenology.

The phenomenological perspective is crucial. In neo-documentation studies, one of our ultimate goals is understanding documents. In Heidegger's (2010) view, ontology is the basis of all philosophical and empirical inquiry. Moreover, the marriage of ontology and epistemology has been a hallmark in the phenomenology of Heidegger and other thinkers, such as Merleau-Ponty (Budd, 2005). If understanding is taken to be an epistemic aim (Greco, 2014), then we can contend that document epistemology must sit upon a sound document ontology. In turn, ontology is only truly possible through phenomenology (Heidegger, 2010). Thus from document phenomenology will spring document understanding. This is consistent with Frohmann's (2004) view that the way forward in "philosophizing about information ... points toward a phenomenology of information and away from a philosophical theory of information" (p. 404).

In this paper, we build on Lund's (2009) proposed framework and Skare's (2009) example in order to present a framework for the phenomenological and holistic analysis of documents. We also address Buckland's (2015) call for attention to the mental aspect of documents by extending the work of Latham (2014) on the phenomenology of documents and Carter (2016) on the role of infrastructure in document experience.

To present this framework, we first clarify what is meant by "holistic analysis" in the next section. We then emphasize that understanding arises through considering diverse perspectives; as an illustration, we describe how this has been achieved in the field of linguistics in order to holistically account for human language. After that, we present a phenomenological framework in two acts: In Act One, we present an analysis of documental transaction, which we see as the coming together of four types of information which cohere into meaning. In Act Two, documents are placed in context: documents have parts, and moreover documents are parts. We argue that the same phenomenological structure exists at all documental frames---documents themselves, parts of documents, and documents in systems. Our purpose in all this is to reveal the fundamental compatibility of different approaches to document studies, offer a coherent terminology with which scholars and practitioners can discuss documents consistently, and invite criticism of our model as the neo-documentalist community works toward a truly holistic way to think about documents.

What is Holistic Analysis?

Analysis is a detailed examination of the elements or structure of something. It is a way to break something into its parts to make the appreciation of it more manageable. At its best, analysis should be done with the constant self-reminder that the parts belong to a whole. This recalls Hegel's (1807/2005) ideal view of scientific development as the cycle of first breaking down concepts into ever-smaller categories, and then putting them back together to gain a holistic understanding.

This vision notwithstanding, sometimes analysis loses the forest for the trees. We use the term holistic analysis to serve as a reminder that all parts that are analysed should be considered not only in and of themselves, but also in relation to each other as parts of an interconnected whole. Moreover, as will be seen further on, entities that may seem "whole" in themselves can, in turn, be seen as parts of progressively more complex wholes.

The notion of holistic analysis may seem oxymoronic. After all, holistic has been defined as: "relating to or concerned with wholes or with complete systems rather than with the analysis of, treatment of, or dissection into parts" (Holistic, adj., 2). Holistic and analytic thinking are seen in the field of psychology as dichotomous modes of cognition. However, the Hegelian dialectic and Heidegger's argument that experience is inseparable from the world in which it manifests, demonstrates the value of iterative analysis with an eye toward holism. Holistic analysis has also been fruitful in other fields; Pross (2012), for instance, described how such thinking has allowed for recent breakthroughs in biology.

Thus we proceed, if oxymoronically, to consider the document through holistic analysis. In this way, we will present a way to understand documents that acknowledges how their physical, mental and social aspects work in concert. In the next section, we discuss how understanding arises from considering something from diverse perspectives; an understanding of documents, then, will likewise be rooted in perspectival diversity.

Understanding Documents

The goal of document analysis, it would seem, is the understanding of the document or documents in question. This viewpoint is echoed by Bawden (2007), who argued that understanding is a more suitable concept as a theoretical basis for information science than knowledge, as understanding connotes a gradation of shades rather than the simple binary of known/unknown. Understanding is achieved through exploring and constructing inferential and explanatory relationships among pieces of knowledge (Briesen, 2014). For instance, to understand how a house fire came about, it is not enough to be told that the cause was "faulty wiring." Rather, one must also know what wiring is, that faulty wiring can cause a short circuit, that a short circuit can generate heat, etc., and moreover be able to see the relationship among these pieces of knowledge. Thus for a better understanding of a particular thing, a system (or systems) of representation must be regarded from diverse perspectives; as these different perspectives are incorporated, a progressively more sophisticated view of the thing is attained, resulting in progressive understanding.

Applying this insight to document studies, we can surmise that, in order to understand documents, we must examine them from diverse perspectives. This has long been implicitly recognized; for instance, Lund's (2004) framework of the document and the ensuing discourse has shown that considering a document from multiple perspectives (physical, mental and social) can lead to better understanding of that document. This points to the need for renewed consideration of these aspects (and possibly others) as a way to further documental understanding.

In attempting to do just this, we have drawn inspiration from the academic discipline of linguistics, which studies the structure of language. In linguistics, it is understood that any given utterance can be analysed in a number of different ways (known in linguistics as levels): the physical aspects of speech sounds, the symbolic aspects of speech sounds, the way sounds combine into meaningful units, the way these units combine into meaningful phrases, the literal meaning of these phrases and the contextual meaning of these phrases. These levels offer different perspectives for considering the phenomenon of language. Language is complex, and diverse research questions can be formulated in studying it; these levels of linguistic analysis offer a way to structure these different questions. A given linguist might only focus on one of these levels in their research, but this common framework allows each linguist to see how their work fits within the wider discipline. Moreover, organizing the study of language in this way facilitates an understanding of language in general. It is our hope that the framework presented below can do the same for document scholarship. However, it should be noted that while we have been inspired by linguistics to consider documents in a new light, we do not propose to transpose the epistemology and structure of linguistics entirely and indiscriminately onto document studies, as doing so may bring along unwarranted assumptions and other perils.

Document Phenomenology in Two Acts

Phenomenology is the study of being. In other words, phenomenology is the letting-be-seen (logos) of things that show themselves in themselves (phenomena) (Heidegger, 2010). As defined by Heidegger, phenomenology is both descriptive and interpretative. In the following sections, we present a framework for the holistic analysis of documents---that is, the interpretation and description of documents---that is, document phenomenology. This framework will be presented in two acts.

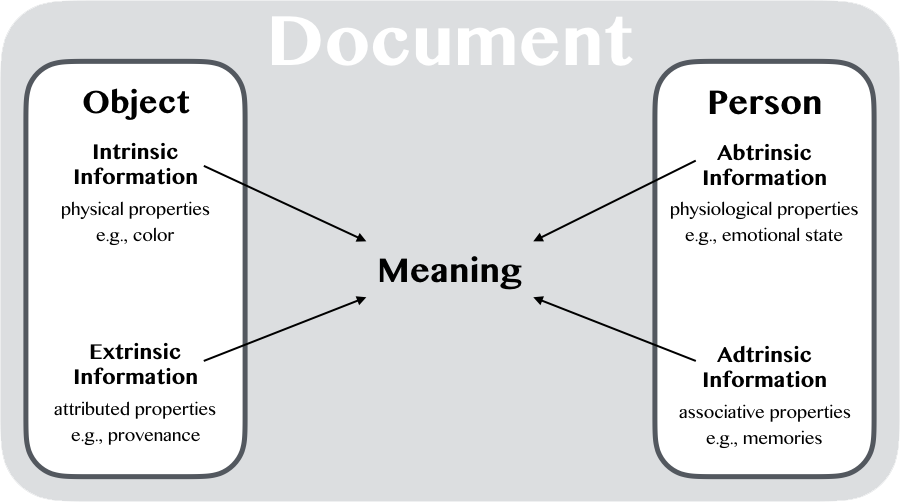

In Act One, we examine documental becoming. This can be viewed as the coming together of four types of information which, in coming together, are made into meaning. This framework builds on Lund's (2009) framework for document analysis, in which the document has three aspects (material, mental, social). Lund's material becomes our intrinsic information and abtrinsic information; his mental becomes our adtrinsic information; and his social becomes our extrinsic information. Moreover, we discuss how information becomes documental meaning.

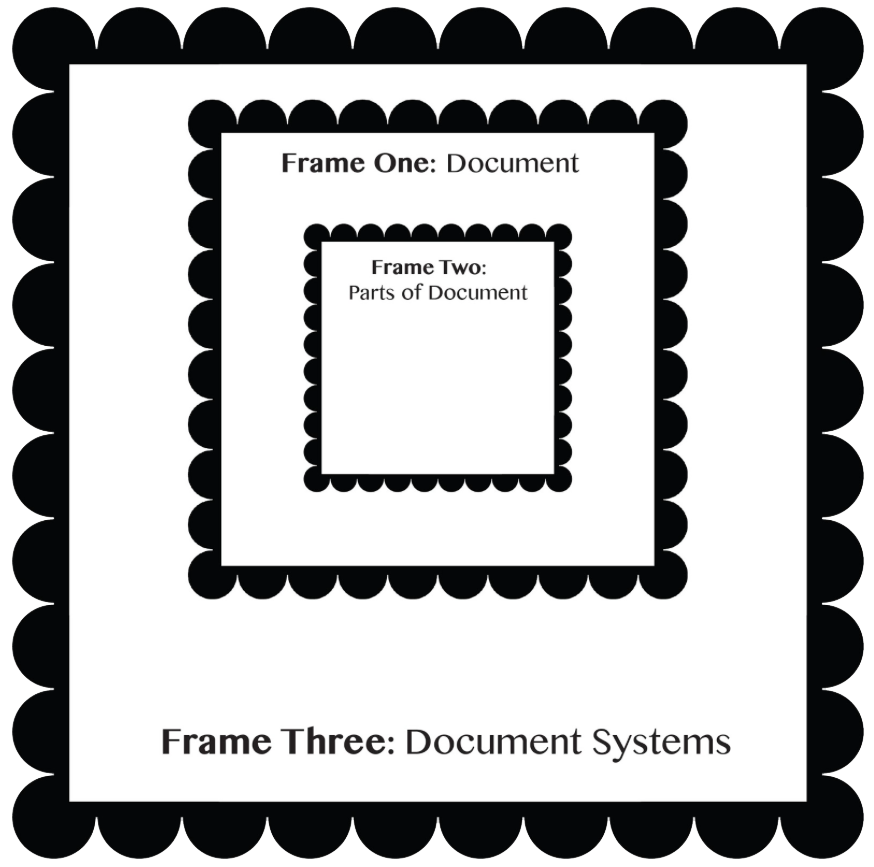

In Act Two, we examine documental being. We present the notion of documental frames: (1) documents themselves, (2) parts of documents, and (3) documents as parts of systems. This framing reveals that the phenomenological structure (presented in Act One) is the same at all documental frames.

Act One: Documental Becoming

A document is only truly a document when an information object is perceived by an agent in a particular context. With no agent, the "document"---what Couzinet (2015) called a "dormant document"---is merely an information object. In the most typical case of a document, the information object is a physical object, and the agent is a human being. Thus, in this paper we use "person" and "object" as a kind of shorthand, not denying that other types of documents exist (e.g., animal--object, person--person).

When the person and the object come together (in present reality, in memory, or in imagination), a transaction occurs (Wood and Latham, 2014). This transaction entails the momentary "fusion" of two whole beings: the person and the object. Thus, in this framework, the object of analysis is always person plus object. The documental transaction has been viewed as the individual's "experience" of the document (Latham, 2014). The term experience here is drawn from Dewey's (1934/2005) aesthetics. For Dewey, "an experience" is singular and meaningful, marked off from the banal procession of everyday experience. Dewey used the term transaction to describe such marked experiences; we extend the use of this term to characterize the coming together of person and object in all documents. Latham (2014) offered a framework for dissecting document experiences, in the form of a continuum of possible experiences with a document that range from efferent (cognitive, logical, intellectual) on one end and aesthetic (emotional, spiritual, holistic) on the other end. Here we add further nuance to that characterization.

Below, we describe the four types of information that contribute to documental meaning. In short, the object furnishes intrinsic information (physical properties) and extrinsic information (attributed properties); the person furnishes abtrinsic information (e.g., related to their psychological state) and adtrinsic information (e.g., memories). These informations are processed by the person; as a result, the four types of information become documental meaning (see Figure 1). As discussed below, meaning is made by humans (individually and socially); it does not exist apart from the person. Some information, however, does exist on its own, which accounts for the continuity and similarity among diverse people's experiences with a given particular information object (observed by Carter, 2016).

Figure 1. Documental elements. Information from the person and object cohere into documental meaning during a transaction.

Because perception is the action through which documents are ascertained, the senses play a central role in documental becoming. These processes are investigated primarily in the field of perceptual psychology (see Gibson, 1986). A person ascertains the object's intrinsic information through the senses (seeing it, hearing it, touching it, tasting it, etc.). In a far-removed way, the senses are also how the object's extrinsic information is apprehended; a person reads, using their visual faculties, about how an object was made, and this information is stored in memory. Sensory memories can likewise be the source of adtrinsic information; the musty smell of an old book can evoke any number of memories. And, of course, the senses may lead to changes in a person's physiological state, possibly contributing to abtrinsic information. Moreover, it is important to note that the senses are seldom passive: We direct our eye movements, we actively turn the pages of a book and we move our bodies as we circle a sculpture. The bodily experience of the human senses, then, are critical to any understanding of a document. But they are not information in themselves; rather, they are modes through which information is transferred.

Making Meaning from Information

Buckland (1997) described documents as being made from the human processing of objects. The first part of this processing is the ascertaining of information through the senses and memory, as described above. Immediately and simultaneously, this ascertaining gives way to meaning-making: the construction of meaning from information.

It is accepted that information is different from meaning, but how it is different is a matter of discussion. To shed light on this distinction, we draw on Bates' (2006, p. 1042) definitions of two levels of information: - Information 1: The pattern of organization of matter and energy (recalling Shannon & Weaver, 1949) - Information 2: Some pattern of organization of matter and energy given meaning by a living being (or its constituent parts)

Meaning, in Bates' view, is a result of interpretation. Meaning is something ascribed to information, actively or automatically, by a person who interprets that information for some purpose; this purpose is generally related to survival, but possibly in a far-removed way (e.g., "surviving" a difficult conversation) (Bates, 2005).

With this grounding, we can establish that information is a pattern of organization prior to consideration. Notably, this does not limit our understanding of information to cognitive information; information can also be corporeal, emotional, or ineffable in nature. Once information is considered and interpreted, it gives way to meaning. When the four types of information-turned-meaning cohere in a transaction experience, the meaning of the document is formed. Thus, we can understand Bates' (2006) two senses of information in a new way: Information 1 is simply informational, while Information 2 is documental.

From the Object: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Information

Objects themselves are characterized by both intrinsic and extrinsic information. Here we define and exemplify both concepts in building the terminology for holistic document analysis, from the point of the individual document transaction.

Intrinsic information

Various philosophical attempts have been made to formally define intrinsicality, but each has its shortcomings. All in all, there seems to be consensus (or at least acquiescence) that intrinsic properties are properties of a thing because of the way the thing is, rather than because of the way anything else is (Weatherson and Marshall, 2014). This is consistent with the notion of intrinsic information described by Ambrose and Paine (2012, p. 191), which refers to the information conveyed by the object itself. In a document, intrinsic information is conveyed through properties such as text, coloration, shape, material and age. As such, time and space are the fundamental dimensions of intrinsic information. As it is intersubjectively observable, communicable and often measureable, intrinsic information lends itself to intellectual, logical analysis. Intrinsic information corresponds to the diachronic attributes described by O'Conner, Kearns and Anderson (2008), which remain the same across time and space. Their synchronic category subsumes the other types of documental information---extrinsic, abtrinsic and adtrinsic---which will be described below.

Extrinsic information

The definition of extrinsicality is simply the converse of intrinsicality. Extrinsic information refers to the socially contextual information associated with an object (Ambrose and Paine, 2012). This information is not conveyed by the object per se, but arises from the study of the object itself in tandem with information from other sources. Extrinsic information often includes a document's provenance and supplemental knowledge about how the object was produced or otherwise came into the world. In this sense, extrinsic information includes information about documentation (Lund, 2004)---that is, the process of how the information object was created. It also includes the diverse practices surrounding a given document, such as what is or was done to or with a document. The analysis of a passport as a document (Buckland, 2014), for example, relies not solely on the content and materiality of the booklet (intrinsic information), but also on outside knowledge about what passports are for and how they are used by travellers and agencies (extrinsic information).

From the Person: Abtrinsic and Adtrinsic Information

Just as objects have dimensions that are internal (intrinsic) and external (extrinsic) to the material of the object, people have dimensions that are, in a certain sense, internal (abtrinsic) and external (adtrinsic). Note that this assertion does not imply Cartesian duality; internal and external should be interpreted abstractly rather than literally: here abtrinsic refers to physical cellular/molecular properties, whereas adtrinsic refers to properties like memory and associations (which arise through functional neuroanatomy).

Abtrinsic information

The term abtrinsic is introduced here as a new coinage. This term was selected for symmetry: just as intrinsic and extrinsic form a pair by way of opposite Latinate prefixes, abtrinsic and adtrinsic (a term extant in the literature, described below) form an analogous pair. Abtrinsic information refers to, in short, information regarding a person's mental state. The details of the human subjective world is not yet well-understood (Chalmers, 1996), though certain mental states have been correlated to the function and presence of neurotransmitters, hormones and other biochemicals. Yet even despite this relative uncertainty, we are not entirely at a loss as to seeing abtrinsic information, at least on a basic level. In this way, precise articulations of the relationship between cognition, emotion, physiology, etc., are not necessary for a basic appreciation of abtrinsic information.

It is easy to imagine, in a practical sense, how the abtrinsic information furnished by a person experiencing extreme hunger would differ from that of a person reeling from the breakup of a long-time intimate relationship and from that of a person presently affected by the deteriorating condition of a hospitalized loved one. Some types of abtrinsic information could be analysed quantitatively through measures such as hormone levels, heart rate and body temperature. Barring access to such measures (and their interpretations), however, abtrinsic information can be analysed indirectly and qualitatively as emotions (e.g., anger, sadness) and feelings (e.g., hunger, pain). In research, this information can be apprehended hermeneutically from phenomenological accounts (van Manen, 2002) of people's experiences.

Adtrinsic information

A person's past and social world also contribute important information to the document experience. Paine (2013) has coined the term adtrinsic information to describe this:

[Adtrinsic information] is information ascribed to an object, rather than derived from studying the thing itself, or certainly known about it. It includes its significance to an individual or to a group, for example grandfather\'s beloved clock, which for the whole family encapsulates his memory; the tree regarded with affection by the whole village, whose felling causes real distress; or the frisson many suddenly lose again when they learn that a painting is fake. (Paine, 2013, pp. 15--16)

Alas, here Paine actually describes what we must understand as adtrinsic meaning rather than adtrinsic information. In the example of Grandfather's clock, the linkage of the artefact to Grandfather's memory is a product of meaning-making; the pieces of adtrinsic information that contributed to that meaning include the fact that Grandfather once owned and cherished the clock, the fact that Grandfather has died, details surrounding the bequeathment of the clock, etc. Adtrinsic information is the personal historical information that comes to the fore through memory associations during a document transaction. This information can be individual (e.g., a childhood injury or a recent meal) and/or social (e.g., a classroom discussion, a president's speech). Indeed, in adtrinsic information, the individual and social are generally intertwined; we experience social encounters from our individual perspective, and we may socially process individual experiences. Thus adtrinsic information arises, immediately and often automatically, from a medley of memory associations. It is the processing of these associations that leads to meaning; this is what Paine described in the passage quoted above. Finally, it should be noted that adtrinsic information interacts fundamentally with abtrinsic information---memories trigger emotions, and vice versa---which is discussed further in the next section.

The Dance of Experience

In the simplest view of a documental transaction, the four types of information come together and, processed by the person, are made into meaning---and action. It is in a document's meaning (which may be unacknowledged by the individual) that evidence or proof, a commonly cited aspect of documents, emerges. Resulting from this meaning is action, which may or may not be externally observable.

This can be illustrated with an example of a woman at an airport holding her boarding pass. The boarding pass is a piece of paper with words and numbers printed on it (intrinsic information) which the woman knows is necessary to allow her passage through security and onto the plane and identify her seat (extrinsic information). The woman is upbeat but perhaps a bit anxious (abtrinsic information), and she is reminded of previous travel experiences (adtrinsic information). All in all, her boarding pass has, in this instance, evidentiary meaning as her ticket to an exciting impending vacation, contributing to the quickening of her pace. These four elements converge to form the document as experienced by the woman.

Yet as even this simple description illustrates, intrinsic and extrinsic information are interwoven (the information printed on the boarding pass relates to the document's social function, and the intelligibility of its inscription relies on social conditioning), and so are abtrinsic and adtrinsic information (memories of prior vacations make the woman all the more excited).

In a sort of dance, the document transaction can leave any of the four types of information altered---a corollary of documental action. For example, intrinsic information is changed when a museum-goer vandalizes a Rothko; extrinsic information is changed when the authenticity of an applicant's college transcript comes into question; abtrinsic information is changed when the sheer attractiveness of a lifelike sculpture causes heart palpitations in a lovesick viewer; and adtrinsic information is changed when a documentary on sweatshop labour forever changes how a person views their clothing.

In this sense, a document experience can be understood as a complex series of transactions. That is, the cohering of information into meaning can be iterative. This reflects Rosenblatt's characterization of reading (as cited in Latham, 2014), which recognizes that the nature of the person's experience can change dynamically as the event unfolds.

It is important to note that this process can be viewed not only in terms of documents but also in terms of parts of documents and systems of documents. One might, for instance, read only a single page out of the thousands that comprise In Search of Lost Time, just as one might peruse the Picasso Museum and encounter dozens of distinct-but-together documents. As we discuss in the following section, the same experiential elements are at play in all documental experiences.

Act Two: Frames of Documental Being

Documents have discernible parts (Lund, 2004, 2009). And, moreover, documents themselves can be seen as parts of larger systems (Carter, 2016; Lund, 2010). We consider these different views as "frames" of analysis in document phenomenology, and we contend that the structure of experience is the same at all frames. This extends Carter's (2016) assertion that document infrastructure can evoke a sense of even larger systems: "organizational structures are mirrored at other levels, influencing how objects are put before users in systematic ways" (p. 72). In this sense, documents can be seen as fractals: the structure of the part is the same as the structure of the whole.

Figure 2. Three frames of documental analysis.

In presenting this view, we draw from Goffman's (1974) frame analysis, which recognizes that a given phenomenon can be "framed" by a variety of perspectives and thus examined in a variety of ways. In this section, we present three frames of document analysis, summarized graphically in Figure 2. In Frame One, we consider documents themselves. In Frame Two, we focus on the parts within a document, which can shed more detailed light on how the different aspects of a document contribute to the total meaning of the document. In Frame Three, we regard the systems in which documents unfold, as in a visitor's experience going through a museum exhibition or a student's experience sifting through a panoply of reference materials. These frames are not mutually exclusive; rather, they are simultaneously manifest. In appearing distinct, they offer an artificial way to delimit an analysis as called for by the researcher's needs.

Frame One: Document

The first frame of analysis reveals the document in its individual entirety.

In everyday life, documents are often considered as singular wholes, undissected and isolated from any larger system. An everyday reader of The Little Prince, for instance, will likely consider that work on its own, not taking into account Saint-Exupéry's other works. A typical viewer of Avatar will likely consider the film as a contained narrative, rather than seeing the characters as actors who also portray other characters in other films. Of course, the nature of a given document can make this the case to a greater or lesser extent. Generally, though, it is only upon deeper analysis, often the purview of experts, that other frames of analysis may be adopted. In this sense, Frame One can be seen as an analytical starting point. In our view, this frame allows the appreciation of the life history of an object---the object's lifeworld (Wood & Latham, 2014)---or, in Frohmann's (2012) words, the documentality of an object, where the object's "entire chain of ... unique traces, from birth to death and beyond" (p. 162) are at issue.

Analysing a document from the frame of that single document itself need not be mutually exclusive from the other two frames, but there are often cases where a single document is used in an analysis. A clear example is found the field of art history. While art pieces are connected over time and space, they are often singled out for analysis, especially when known artists are involved. In a survey course, for instance, single pieces are drawn out and analysed as singular wholes. "Today," the syllabus might seem to say, "we will discuss Descent from the Cross by van der Weyden, tomorrow The Birth of Venus by Botticelli, and later Nightwatch by Rembrandt and Guernica by Picasso."

Another field that sometimes focuses on individual documents is archaeology. There are certain subsets of the field that take the document itself as its point of departure. For instance, some lithic analysts study Paleo-Indian projectile points---stone tools from early American inhabitants---in terms of production technique, style and alterations. Other aspects of the Paleo-Indian lifeways aren't necessarily considered, as the focus is on the tool itself.

There are many other examples of analyses that involve single documents. Astronomers study single stars, appraisers of art or coins or furniture also focus on single documents, museums often single out an object for consideration, and even works in document studies have recently featured singular objects such as the passport or birth certificate as a focal point.

Frame Two: Parts of Documents

Whereas in the first frame we considered documents in their individual totalities, in this frame we examine the parts of an individual document. It may be critical for a researcher in some cases to analyse how the individual components of a document contribute to the overall document, accounting for each of those components as well as the whole.

This section presents a framework for exploring parts of a document; analysis of these parts can reveal how documental information is formulated. We first expound on the notion of doceme (Lund, 2004) and then introduce a new concept: doc. Docemes are any parts of a document (aspects of any of the four types of documental information that make up the document). Docs are potential docemes consisting only of physical material; they can be thought of as corresponding to Bates' (2005) Information 1, whereas docemes correspond to Bates' Information 2. Docs are important because they are the purview of a number of disciplines (e.g., preservation, computational vision modelling, biology) that are not within document studies proper; the concept demonstrates where these allied disciplines are related to document studies.

Docemes

The term doceme was originally introduced by Lund (2004) in his framework for document analysis (documentation, document, doceme); this section expands upon and further contextualizes Lund's concept.

The suffix -eme is now used to describe atomistic concepts in numerous fields of study, but it has its origins in the concept of the phoneme in linguistics (Pike, 1954/1967). As such, the notion of doceme presents an opportunity for the exploration of analogies with the phoneme.

As described by Lund (2004), a doceme is "any part of a document, which can be identified and analytically isolated, thus being a partial result of the documentation process" (p. 99). He cites, as an example of a doceme, a photograph within a textual article, wherein the text and the photograph together comprise the complete document. As Lund asserts, docemes cannot exist in the same capacity outside documents as they do within them, just as phonemes can never exist outside languages.

It should be noted that a related concept in linguistics is the morpheme, which is a grouping of phonemes. There is no need for a documental analogy to the morpheme, however. Language has made use of these concentric concepts because languages have a finite number of phonemes that must be used to express an infinite number of meanings; the morpheme offers a stepping-stone on the way toward the infinitude of expression. In documents, on the other hand, there are infinite docemes at our disposal, so such a stepping-stone is not necessary.

The notion of doceme is very flexible; specific docemes can be delineated according to an analyst's needs and the nature of the document in question. For example, if a given textbook is the document under study, a chapter of that book could be considered a doceme. And within that chapter, a section could be considered another doceme. And within that section, a figure could be another doceme. And within that figure, which includes a photograph and a caption, the photograph itself could be considered a doceme. (It should be noted that these are not exactly analogous to the concentricity of morphemes and phonemes because they are not constrained, whereas morphological and phonological systems are highly constrained.)

Lund (2004) only described docemes derived from the information object itself---that is, comprising parts of the document's intrinsic information. Other examples of such docemes include the arm of a Greek sculpture or a scene from a film. It may be the case that these intrinsically informational docemes are the most important type of doceme to the wealth of document scholars, but it is important to note that other types of docemes can be analytically isolated, stemming from extrinsic, abtrinsic or adtrinsic information. For example, if we consider a person watching Star Wars: The Force Awakens as a document, innumerable docemes can be identified. A few include: - the text of the opening crawl (intrinsic information) - knowledge about the film's box office gross (extrinsic information) - anger directed toward the First Order (abtrinsic information) - memories of a critical review the person read prior to viewing the film (adtrinsic information)

In terms of analysis, docemes can be analysed in the same way that document experiences are analysed, described in Act One above, and the process can be iterative. For instance, if a given doceme consists of the extrinsic information of an overarching document, that information is the intrinsic information in the context of the doceme; the doceme also includes extrinsic, abtrinsic and adtrinsic information that arise when the doceme is experientially isolated. For a concrete (or rather, marble) example, consider the sculpture David by Bernini as a document. As we have conceptualized it here, this document consists of an individual's encounter with the sculpture at the Villa Borghese in Rome. This document includes any number of docemes, all of which fall into the four informational categories of intrinsic, extrinsic, abtrinsic and intrinsic information. One doceme is the name "David" itself, which is extrinsic information. Now that this information has been analytically isolated, it can be analysed as a document in itself: intrinsically, it consists of the phonemes or letterforms that compose "David"; extrinsically, it may consist of, for instance, the Biblical story of David; abtrinsically, it may consist of the individual's mental strain in trying to remember whether David was canonized a saint or not; adtrinsically, it may consist of memories of a recent trip to Florence, where another marble sculpture called David was encountered.

The notion of doceme can offer a granular level of nuance to the analysis of a document: if a document is split into two docemes, the four types of information can be articulated for each of those docemes, and then they can be brought together, revealing a deeper understanding of what the complete document means.

Docs

Our discussion of the doceme as analogous to the concept of phoneme in linguistics presupposes the existence of an analogy to the linguistic concept of phone: the doc. This word is a new coinage; it derives from the word "document" in a way that is analogous with "phone."

In linguistics, phones are speech sounds as understood independent of any language. Phones are analysed for their physical properties (amplitude, waveform, frequency, etc.) and their auditory perception (how the brain and ear work in concert). Phonemes, on the other hand, are speech sounds that are understood as components in a language system and thus for their symbolic value. Phonemes are examined for how they can be combined and substituted to form and change meaning. While the notion of phone exists outside any language, the notion of phoneme can only refer to a given language. (For example, one can discuss the phonemes of the English language, but not the phones of the English language.) Not all human languages take advantage of all possible sounds; tongue clicks, for example, are phonemes only in some African languages and are not phonemes in, say, English. Moreover, there are phones that humans can produce but are not realized as phonemes in any human language---nasal snorts, for example.

Docs, then, are the physical components that make up any document, irrespective of information or meaning. They can come from the object (in the form of component materials) or the human (in the form of, for example, hormones). In this sense, they can be understood as solely the intrinsic aspects of a doceme. Because documents and docemes are quite diverse, so are docs. Considering a book, a few of the docs that might be analysed include: the paper, the ink, the covers, the colours and the letterforms. Considering a painting, a few of the docs that might be analysed include: the support, the paint and the size. In practice, any material component could be considered a doc, either because it is found as a component in an existing document, or because it could be used as such.

In this way, docetic (the adjectival form of doc) analysis allows for the consideration of materials not yet used in documentation but which could be, in a future possible (or presently science-fiction) world, such as extreme light frequencies and encoded heartbeats. To elaborate an example, hydrolysed uranium is a physical substance in our world, and it could conceivably be used as a material component in some sort of document. To our knowledge, though, this has not been done, and there is not (yet) a culture that exchanges information via hydrolysed uranium documents. Thus hydrolysed uranium can be seen as a doc but not (yet) a doceme. This perspective could, though, conceivably lead to scientific advances that allow for hydrolysed uranium documents, if it should be deemed useful to employ hydrolysed uranium in this way

As a rule of thumb, things that can be considered as docs can also be considered as docemes. It is not an either--or question---the two notions are not mutually exclusive; they are merely different ways of conceptualizing a phenomenon. When something is considered as a doc, it is understood as a physical manifestation, disregarding context. A doceme, on the other hand, is an aspect of a document that contributes some meaning to that document.

Docetic analysis can also be used to understand how documents are produced and how they change over time. Such analysis can inform, for example, producers of documents, as well as archivists, conservators and bibliographers. In this way, the recognition of the doc allows the disciplines interested solely in the physical/objective properties of documents to be united under a common vernacular.

This discussion recalls Manovich's (2001) assertion that "the discrete units of modern media are usually not the units of meanings, the way morphemes are. Neither film frames nor the halftone dots have any relation to how film or a photographs affect the viewer" (p. 29). As a blanket statement, this is, of course, debatable. However, we can point out that Manovich here is examining film frames and halftone dots as docs rather than as docemes; an in-depth example of such an analysis is given by Anderson, O'Connor and Kearns (2007). Were we to explore how these aspects of documents can, indeed, impact meaning, we would be considering them as docemes. For example, a docemic (the adjectival form of doceme) analysis of film frames might explore how the "same" film presented in different aspect ratios conveys different information and leads to different meaning.

Likewise, Drucker (2014) points out that "theories of vision ... and, even more, those of optics (the science of light, color, and instruments) belong to the history of scientific investigation of the physiology of sight and the phenomena of the visual world" (p. 48) and, in our framework, fall under docetic analysis, whereas "the study of Gestalt principles, design and compositional rules, and visual tendencies are rooted in interpretative activity" (Drucker, 2014, p. 48) and are docemic in nature.

This section presented a way to analyse document components, through the concepts of docemes and docs. Docemes are parts of a given document as perceived in the experience of that document (or, at least, part of it). Transactions with docemes can be analysed in terms of intrinsic, extrinsic, abtrinsic and adtrinsic information and meaning, just as transactions with whole documents can. Docs represent solely intrinsic information, and they need not be existent in any actual document---rather, any material component that could be used in a document can be considered as a doc. Docs are generally within the purview of materials science, and they offer a bridge between document studies and these other disciplines. Moreover, they invite consideration into the development of novel---and potentially revolutionary---types of future documents.

Frame Three: Documents As Parts of a System

Documents function within shared systems (e.g., families, organizations, cultures). Indeed, a document can be said to exist by virtue of its arrangement with other things (Briet, 1951/2006). Therefore a holistic understanding of documents must consider them contextually---or, more precisely, relationally---within infrastructural systems (Carter, 2016; see also Appadurai, 1986; Baudrilliard, 1968/2006; and Miller, 1987). Within these systems, documents are perceived and used in various ways, depending on their relationships with other documents, systems and people (Brown and Duguid, 2000), and are situated both spatially and temporally (Frohmann, 2004). A single document (or document transaction), then, can be interpreted differently depending on the context in which it is discussed, the relationships that emerge from this contextual locus, the time in which it is considered, and the geocultural space within which it is discussed. This is consistent with Frohmann's (2012) assertion that documentality---a document's power or agency---arises by virtue of a document's arrangement with other things in a specific context and tradition (see also Latour, 1992). Ferraris (2012) also uses the term documentality, but conceives of it slightly differently, as a "theory of the social world" (p.1). Both authors are referring to the shared networks in which documents manifest.

Carter (2016) showed the relevance of infrastructure studies to document experience, as "focusing on the systems that bind together objects, recipients and producers allows a better understanding of experience as shared by individuals who exist in relation to similar sociotechnical systems" (p. 66). This view allows us to appreciate that all documents exist within larger systems, even beyond what is traditionally considered sociotechnical. Reading a book, a person is cognizant---at some times more than others, depending upon what frame of analysis they are using---that other books exist and that this book is one of them, that this book falls within a particular genre, that it was written during a particular era, that its author had particular attitudes toward particular things... all of which can colour the reader's experience of the book. Looking at a particular book as an individual whole, we can learn some things. Looking at individual docemes within it, we can learn other things. Looking at that book as part of the larger world of books, we can learn still other things.

To illustrate how document systems can be analysed in terms of the four types of information described in Act One above, we can consider the example of a gallery space in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in which a number of works by Duchamp are installed. On one wall, there is a large board with a paragraph about Duchamp and his legacy. Alongside each of the artworks in the room is a small placard describing that work. As a person moves about the room, documental information is revealed in numerous ways:

- Intrinsic: The person appreciates the physical properties of the art pieces, the arrangement of the pieces, installation, lighting in the room...

- Extrinsic: The person reflects on the placards, the audio guide, what they already knew about Duchamp going in...

- Abtrinsic: The person hasn't eaten all day and is really hungry. Also they just got some disconcerting feedback on a paper they wrote, and this keeps coming to mind. And they have a blister on their foot, so every step through this gallery kind of hurts and the person would like to sit but there are no benches...

- Adtrinsic: The person studied art history in high school and is brought back to their discussion on Duchamp's Fountain and how that challenged their conception of what art is. They remember other art galleries they've been in and how they were lighted differently...

Of course, this is only a broad view. The experience of this system of documents could be further parcelled out into its manifold transactions, moment by moment, as the human moves about the room continually perceiving the environment.

Despite the tripartite nature of this framework, as we understand it there are not merely three frames of document phenomenology. Rather, documents exist in an infinity of frames. Indeed the entire universe can be seen as a living, breathing document. How that document is framed is rather arbitrary; again, the researcher should do so as befits their research questions. This framework is suggested as a device to help document scholars and practitioners communicate about documents. This outlook also aims to help us understand digital documents and other new and complex documental formats. Facebook, for example, has been contemplated from the perspective of document studies (Skare and Lund, 2014): How should Facebook as a document be considered? That is, is each individual post a document? Is a person's timeline a document? Is all of Facebook one mammoth document? We contend that all of the above are valid analyses, as parts of documents, and as systems of documents, depending on the framing.

Conclusion

In this paper, we presented a framework for the holistic analysis of documents, expanding on previous conceptualizations. We drew lessons from phenomenology and linguistics in order to present a fuller framework, introducing a number of new analytical terms. In so doing, we have offered a cohesive, consistent vocabulary for document scholars of all kinds. In the framework of document experience presented here, a document manifests in an encounter between an object and a person---a transaction. From the object, intrinsic information and extrinsic information are present; from the person, adtrinsic information and abtrinsic information are present. In the document transaction, these elements are interpreted and become meaning.

Based on this discussion, the document emerges as part of a multi-dimensional structure which can be analysed using frames that focus on individual documents, document parts, and the networks within which documents are enacted. When considering the analysis of a document or documents, one can begin with the whole picture of document experience. Or a researcher could focus on aspects of the document itself. The most atomistic component of a document is the doc, which carries only intrinsic information. Next are docemes, which can be understood as docs that also have extrinsic information and can engender transaction experiences when beheld by a person. Finally, documents can be understood as parts of systems, the complex networks of relationships that exist between documents and people and the societies in which they live. We hope that the shared terminology this framework provides will bring clarity as document researchers analyse documents at diverse frames. Moreover, we hope it will lead to further discussion and ultimately education regarding document literacy, which is becoming increasingly important in our wider society and which document studies is uniquely positioned to champion (Buckland, 2005).

Though we have focused on documental phenomenology as experienced by individuals (which has been largely unexplored in the literature, as discussed above), we recognize that this is not the only perspective from which documents can be understood. Explorations of social phenomenology might be a fruitful path for further research, for example. In this light, we invite the use and critique of our model as document scholars and practitioners work toward a truly holistic way to think about documents.

References

Anderson, R. L., O'Conner, B. C., and Kearns, J. L. (2007). "The functional ontology of filmic documents", in Skare, R., Lund, N.W., and Vårheim, A. (Eds.), A Document (Re)turn: Contributions from A Research Field in Transition, Peter Lang, Berlin, Germany,

Ambrose, T. and Paine, C. (2012), Museum Basics, 3rd ed., Routledge, Abingdon, UK.

Appadurai, A. (1986), "Introduction: commodities and the politics of value", in Appadurai, A. (Ed.), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, Cambridge University Press, Cambridgeshire, UK, pp. 3--63.

Bates, M. J. (2005), "Information and knowledge: An evolutionary framework for information science", Information Research, Vol. 10 No. 4, paper 239, available at: http://informationr.net/ir/10-4/paper239.html (accessed 21 January 2016).

Bates, M. J. (2006), "Fundamental forms of information", Journal of the American Society for Information Science, Vol. 57 No. 8, pp. 1033--45.

Baudrilliard, J. (2006), The System of Objects, Verso, London (original work published 1968).

Bawden, D. (2007), "Organised complexity, meaning and understanding", Aslib Proceedings, Vol. 59 No. 4/5, pp. 307--27.

Briesen, J. (2014), "Pictorial art and epistemic aims", in Klinke, H. (Ed.), Art Theory as Visual Epistemology, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK, pp. 11--27.

Briet, S. (2006), What is Documentation? English Translation of the Classic French Text (trans. by Day, R.E. and Martinet, L.), The Scarecrow Press, Lanham, MD (original work published 1951).

Brown, J. S. and Duguid, P. (2000), The Social Life of Information, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Buckland, M. (1997), "What is a 'document'?", Journal of the American Society of Information Science, Vol. 48 No. 9, pp. 804--9.

Buckland, M. (2005) "Information schools: a monk, library science, and the Information Age", in Hauke, P. (Ed.), Bibliothekswissenschaft -- Quo Wadis? De Gruyter, Munich, pp. 19--32.

Buckland, M. (2014), "Documentality beyond documents", The Monist, Vol. 97 No. 2, pp. 179--86.

Buckland, M. (2015), "Document theory: an introduction", in Willer, M., Gilliland, A. J. and Tomić, M. (Eds.), Records, archives and memory: selected papers from the Conference and School on Records, Archives and Memory Studies, University of Zadar, Croatia, May 2013, University of Zadar Press, Zadar, Croatia, pp. 223--37, preprint available at: http://capstonex.com/assets/zadardoctheory.pdf (accessed 21 January 2016).

Budd, J. M. (2005), "Phenomenology and information studies", Journal of Documentation, Vol. 61 No. 1, pp. 44--59.

Carter, D. (2016), "Infrastructure and the experience of documents", Journal of Documentation, Vol. 72 No. 1, pp. 65--80.

Chalmers, D. J. (1996), The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK.

Couzinet, V. (2015), "A documentologic approach of herbarium: documentary anabiosis and phylogenetic classification", Proceedings from the Annual Meeting of the Document Academy, Vol. 2, paper 16, available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/docam/vol2/iss1/16 (accessed 21 January 2016).

Dewey, J. (2005). Art As Experience, Minton, Balch & Company, New York, NY (original work published 1934).

Drucker, J. (2014), Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Ferraris, M. (2012), Documentality: Why It Is Necessary to Leave Traces (trans. by Davies, R.), Fordham University Press, Bronx, NY.

Frohmann, B. (2004), "Documentation redux: prolegomenon to (another) philosophy of information", Library Trends, Vol. 52 No. 3, pp. 387--407.

Frohmann, B. (2012), "The documentality of Mme Briet's antelope", in Packer, J. and Crofts Wiley, S. B. (Eds.), Communication Matters: Materialist Approaches to Media, Mobility and Networks, Routledge, New York, NY, pp. 173--82.

Gibson, J. J. (1986), "The theory of affordances", in The Ecological Approach to Perception, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 127--43 (original work published 1979).

Goffman, E. (1974), Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Gorichanaz, T. (2015), "For every document, a person: a co-created view of documents", Proceedings from the Annual Meeting of the Document Academy, Vol. 2., paper 9, available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/docam/vol2/iss1/9 (accessed 21 January 2016).

Greco, J. (2014), "Episteme: knowledge and understanding", in Timpe, K. and Boyd, C. E. (Eds.), Virtues and Their Vices, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 285--301.

Hegel, G. W. F. (1807/2005). Hegel's Preface to the "Phenomenology of Spirit" (trans. by Yovel, Y.), Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, (original work published 1807).

Heidegger, M. (2010), Being and Time (trans. by Staumbaugh, J. and ed. by Schmidt, D. J.), State University of New York Press, Albany, NY (original work published 1927).

"Holistic, adj", [Def. 2]. (n.d.). In Merriam--Webster, available at: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/holistic (accessed 21 January 2016).

Janouch, G. (1971), Conversations with Kafka (trans. by Rees, G.), Penguin, New York, NY.

Latham, K. F. (2012), "Museum object as document: using Buckland's information concepts to understand museum experiences", Journal of Documentation, Vol. 68 No. 1, pp. 45-71.

Latham, K. F. (2014), "Experiencing documents", Journal of Documentation, Vol. 70 No. 4, pp. 544--61.

Latour, B. (1992), "Where are the missing masses? The sociology of a few mundane artifacts", in Bijker, W. E. and Law, J. (Eds), Shaping Technology / Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 225--58.

Lund, N. W. (2004), "Documentation in a complementary perspective", in Boyd, R.W. (Ed.), Aware and Responsible: Papers of the Nordic-International Colloquium on Social and Cultural Awareness and Responsibility in Library, Information and Documentation Studies (SCAR-LID), Scarecrow Press, Lanham, MD, pp. 93-102.

Lund, N. W. (2009), "Document theory", Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, Vol. 43, pp. 399--432.

Lund, N. W. (2010), "Document, text and medium: concepts, theories and disciplines", Journal of Documentation, Vol. 66 No. 5, pp. 734--49.

Lund, N. W. and Buckland, M. K. (2009), "Document, documentation, and the Document Academy: introduction", Archival Science, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 161--4.

Manovich, L. (2001), "What is new media?", in The Language of New Media, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 18--41.

Meyriat, J. (1981), "Document, documentation, documentologie", Schéma et Schématisation, Vol. 2 No. 14, pp. 51--63.

Miller, D. (1987), Material Culture and Mass Consumption. Basil Blackwell, Oxford, UK.

O'Connor, B. C., Kearns, J. and Anderson, R. L. (2008), Doing Things with Information: Beyond Indexing and Abstracting, Libraries Unlimited, Westport, CT.

Paine, C. (2013). Religious Objects in Museums: Private Lives and Public Duties, Bloomsbury Academic, London, UK.

Pike, K. L. (1967), Language in Relation to a Unified Theory of Human Behavior, Mouton, The Hague, Netherlands (original work published 1954).

Pross, A. (2012), What Is Life? How Chemistry Becomes Biology, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Shannon, C. E. and Weaver, W. (1948), The Mathematical Theory of Communication, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL.

Skare, R. (2009), "Complementarity -- a concept for document analysis?", Journal of Documentation, Vol. 65 No. 5, 834--40.

Skare, R. and Lund, N. W. (2014), "Facebook -- a document without borders?", Proceedings from the Annual Meeting of the Document Academy, Vol. 1, paper 7, available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/docam/vol1/iss1/7 (accessed 21 January 2016).

van Manen, M. (2002). Writing in the Dark: Phenomenological Studies in Interpretive Inquiry, Althouse Press, London, ON.

Weatherson, B. and Marshall, D. (2014). "Intrinsic vs. extrinsic properties", in Zalta, E. N. (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2014 Edition), available at: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2014/entries/intrinsic-extrinsic (accessed 21 January 2016).

Wood, E. and Latham, K. F. (2014), The Objects of Experience: Transforming Visitor--Object Encounters in Museums, Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.