Gorichanaz, T. (2019). Information experience in personally meaningful activities. Journal of the Association for Information Science & Technology, 70.

Abstract. Information behavior in activities that are freely chosen has been

little explored. This paper conceptualizes personally meaningful

activities as a site for information behavior research. Personal meaning

is discussed as a necessity for human being. In the information age,

there is an ethical directive for developers of information technology

to promote and afford personally meaningful activities. This paper

builds on discussions of the pleasurable and profound in information

science conceptually and empirically. First, it argues for the necessity

of phenomenology in these discussions, which heretofore has been mostly

absent. Next, it presents results from a qualitative, empirical study on

information in personally meaningful activities. The empirical study

uses interpretative phenomenological analysis to examine information

experience in three domains of personal meaning: Bible reading,

ultramarathon running, and art-making. The following themes emerge and

are discussed: identity, central practice, curiosity, and presence.

Opportunities for technological development and further research are

outlined.

Introduction

Oftentimes we engage with information because we have to, not because we

want to. Concomitantly, the preponderance of research in information

behavior has focused on information activities that people are to a

greater or lesser extent compelled to undertake. But what about those

activities which are freely chosen?

Friedrich Schiller (1795/2004, p. 80) maintained that "Man plays only

when he is in the full sense of the word a man, and he is only wholly

Man when he is playing." Playing here is not being frivolous; rather,

it is engaging with the world—discovering personal meaning. These are

the sort of activities we live for, to be completely ourselves, and so

a complete account of information behavior must contend with them as

well. Moreover, the promotion of such activities can be interpreted as

an ethical directive, one rooted in the landscape of evolutionary

psychology; thus the field of information behavior should be concerned

with such information activities if it is to be concerned with ethical

action.

In this paper, I attempt a move in that direction. I conceptualize the

information activities we choose as personally meaningful information

activities, building principally on the landmark paper of Kari and

Hartel (2007), "Information and the Higher Things in Life." Crucially, I

argue that phenomenology is necessary for this concept to be

coherent—that is, we must look at information experience. This

discussion grounds a study of three different personally meaningful

information activities, from which shared themes emerge.

First, a terminological note. I understand meaning to be coordinating

action toward goals, following Floridi (2011). Meaning is thus a

property of a system. To speak of human experience, meaning can be

described as the way patterns of neural activity "evoke feeling-thinking

responses in us" (Johnson, 2007, p. 243). Personal meaning, then, is

that meaning which contributes to one's being a person. I understand

person, in turn, following Harré (1998, p. 73), to be "a word for a

human being as a social and psychological being, as a human organism

having a sense of its place among others of its kind, a sense of its own

history and beliefs about at least some of its attributes." So personal

meaning is found in a situation that contributes to such factors as

well-being and uniqueness (Harré, 1998). Though it has not yet, to my

knowledge, been discussed in information science, the concept of

personal meaning has a significant lineage in psychology and allied

fields (Frankl, 1946/2006; Peterson, 1999). Given the central role that

information technology plays in modern life, it seems clear that it is a

topic of interest to information science as well.

Information Ethics and Personal Meaning

From the perspective of information ethics, one of the purposes of human

life is flourishing. This viewpoint can be traced back to Wiener (1954),

to say nothing of the philosophical discourse on the matter that

predates information ethics or cybernetics. According to Wiener, for

human beings to flourish they must be free to engage in creative and

flexible actions that allow the fullest realization of their potential

as intelligent, decision-making agents. Wiener distills this vision in

his great principle for justice, which articulates a need for individual

liberty to pursue those aims that one finds personally meaningful. In

the psychological framework developed by Baumeister (1991), personal

meaning can be described along four dimensions: purpose, efficacy, value

and self-worth. The pursuit of personal meaning, to be sure, relies on

information access, processing and understanding, as well as a

particular experiential dimension of information activities.

Some may hope for a utopia where people are free to do only that which

they find personally meaningful. Others, surely, would caution that the

very idea of utopia is incoherent. Regardless, it seems to be the case

that today many people spend much of their lives engaged in information

activities that they do not find personally meaningful. Mills (1953),

for example, identified a trend toward the meaninglessness of work in

American society, particularly as it became more information-based: less

and less were people allowed to decide for themselves what to do at work

and how to do it. For Mills, this led to the separation of work from

everyday life. In this world people are "working for the weekend," as

the pop song goes. This split endures even today, as we tend to

conceptually separate work from everyday life; in our field, this is

visible in the discourse on everyday life information activities, which

are distinguished from those related to work (see Savolainen, 1995).

Mills (1953) suggests that work can be made more personally meaningful

if it can be infused with a craft ethic. In Mills' time, such an ethic

already characterized the work of a privileged few, such as

intellectuals and artists; decades later, Csikszentmihalyi (1975/2000)

would show this in his research on flow experiences, which challenged

the separation between "work" and "play" in many domains. Hammell

(2004), in the field of occupational therapy, concurs that it is

possible for a person's occupation to contribute to personal meaning and

quality of life, even though research has tended to emphasize only how

occupations meet extrinsic needs (e.g., monetary success). On Mills'

view, however, this craft ethic should be made much more broadly

accessible. Csikszentmihalyi, Hammell and Wiener would seem to agree.

Thus, in reaching for a more ethical information society, we should seek

to infuse more of our information activities with deeper personal

meaning. This requires understanding better what makes some information

activities personally meaningful.

To this end, Dreyfus and Kelly (2011) discuss how personal meaning can

be cultivated. Finding meaning, in their view, is a matter of nurturing

the skill for encountering the sacred in the world. They invoke the

Greek concept of poiesis—craft, or "making," though not in the sense

of techne—which entails both passive and active components:

passively, poiesis denotes being receptive to what is given in the

world; actively, it involves the trained judgment of decision-making.

Dreyfus and Kelly argue that opportunities for poiesis abound, even in

what may seem to be drudgery, and that seizing them is our prerogative.

As an example, they describe the making of one's morning coffee. As an

everyday task, relegated by many to Mr. Coffee or Starbucks, making

coffee could easily be mindless and meaningless. But, with poietic

attention—that is, with a craft ethic—making coffee could

alternatively be a site for personal meaning: selecting particular

beans, grinding them in a certain way, preparing the coffee in a

distinct manner, etc., all offer opportunities for poiesis both passive

and active. Then, drinking the coffee presents another host of

opportunities: sitting in a comfortable place and manner, using a

special vessel, savoring the aroma, appreciating the color, etc.

Conceptually, what can make coffee (or anything) a site for poiesis is a

person's learning to make distinctions that matter to them:

When one has learned these skills and cultivated one's environment so

that it is precisely suited to them, then one has a ritual rather than

a routine, a meaningful celebration of oneself and one's environment

rather than a generic and meaningless performance of function.

(Dreyfus & Kelly, 2011, pp. 218–219)

Thus personal meaning can emerge from the craft ethic: applying a

particular mindset to a task at hand. This can be applied even to work,

which may otherwise be devoid of personal meaning. Recently, in a book

on business productivity for a general audience, Newport (2016)

describes how a craft ethic can be applied to mastering a wide variety

of skills through deliberate practice and focused "deep work," which

improves one's sense of personal meaning.

If this can be accomplished, then people would be able to develop their

selves in a more integrated way. This constitutes a move toward

self-care, which is an important ethical directive in the information

society (see Capurro, 2000; Floridi, 2013; Foucault, 1988). This is not

a solipsistic or egotistical claim; rather, it is the recognition that

without a good self, good work for others is not possible, as formulated

in the Christian maxim to remove the log from your own eye before

fussing over the speck in your brother's (Matt. 7:5), as well as the

airline injunction to secure your own oxygen mask before helping others;

it is the recognition that all beings are connected (in an ontic

trust; see Floridi, 2013), but that certain actions must be directed by

agents toward themselves for the subsequent betterment of all. As an

aside, it may be worth noting that this idea has footing in many

philosophical schools besides information ethics, such as (to name a

few) in the spiritual exercises of antiquity (Hadot, 1995),

transcendentalism (Cafaro, 2004), and recent synthesizing work by Wright

(2016).

Personal Meaning and Information Behavior

Starting with the Pleasurable and Profound

Kari and Hartel (2007) identified that information activities occur in

contexts that can be categorized as lower and higher. Lower contexts

include everyday life (in the sense of "going with the flow") and

problem solving, and they are neutral or negative in nature. Higher

contexts include pleasurable and profound activities; they "are the

special 'ingredients' that make human life meaningful, shape our very

identity, and give us the reason to live in the first place" (Kari &

Hartel, 2007, p. 1133). According to Kari and Hartel, information

science has historically been preoccupied with investigating information

in the lower contexts to the exclusion of the higher ones. Kari and

Hartel aim to stoke research on information in the higher things. As

part of their conceptual analysis, they present a number of themes they

find to be characteristic of higher-context activities, including

internal motivation, achievement, projects, meaning, and interest.

Kari and Hartel (2007) recognize that "there is in all likelihood

nothing inherently higher or lower about information as such. Rather,

its 'height' is determined by its content, source, channel, and context"

(p. 1139). They do not go into detail on how these factors contribute to

"height," but they do offer an illustration that "from an objective

vantage" (p. 1140) would seem to be lower-context information, but which

could in fact be higher-context if the person "circulates the message of

his own accord, as a part of his life mission" (p. 1140).

The Role of Phenomenology

What Kari and Hartel (2007) thus imply but do not name explicitly is

that the "height" of information is a phenomenological description. That

is, it must be understood from the first-person perspective of the agent

beholding that information, taking into account their lived situation.

In other words, it is an experiential description. To take Kari and

Hartel's work further, the phenomenological aspects of their theory

should be brought to the fore and further developed. This can bring

clarity to how information and knowledge can be keys to a better life

(on this point they cite Nicholson, 2002), which Kari and Hartel say is

not understood well.

At the time of Kari and Hartel's writing, there was not a very strong

tradition of phenomenology in information science (much less information

behavior) research. This is not to overlook the early conceptual work by

scholars such as Budd (1995, 2005), but simply to point out that it had

not yet percolated into the broader consciousness of the information

science research community. In the past decade, there has been a

smattering of phenomenological information research, and interest in the

metatheory seems to be increasing. A panel at the 2016 installment of

the Conceptions of Library and Information Science conference (Vamanu,

Gorichanaz, Latham & Suorsa, 2016) brought together some of the

literature on the topic in grounding a discussion meant to foment

further phenomenological research. It is beyond the scope of this

article to survey all this research; it should be noted, simply, that

the contribution of phenomenology to information science has long been

overlooked by the majority, and that this is beginning to be recognized.

This article contributes to this current of understanding.

Conceptualizing Personally Meaningful Information Activities

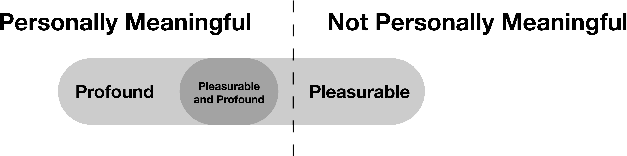

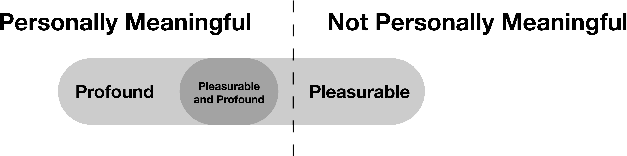

Based on the discussion so far, we can define personally meaningful

information activities as those information activities that a person

carries out freely and for their own purposes, and which reinforce the

person's senses of efficacy, value and self-worth. Given that Kari and

Hartel (2007) bisected the higher contexts into the pleasurable and

profound, we might ask how these two concepts relate to personal

meaning. It seems to me that all higher contexts are personally

meaningful, and thus "personally meaningful information" could be

equated with "higher information." Profound and pleasurable are

certainly descriptors of some personally meaningful activities. An

activity could be profound without being pleasurable, but probably not

without being personally meaningful (e.g., grieving); an activity could

be pleasurable without being personally meaningful or profound (e.g.,

pure hedonism); and an activity could be personally meaningful without

being pleasurable (e.g., extreme physical exertion) or profound (e.g., a

small activity, such as deciding to buy a handmade notebook rather than

a mass-produced one). Thus we find ourselves with a conceptual scheme

such as that in Figure 1. This shows that Kari and Hartel (2007) did

identify a sweet spot in looking at the overlap of the pleasurable and

profound. However, it also suggests that there may be additional

concepts within the umbrella of personally meaningful that are waiting

to be uncovered. In my view, this uncovering will require further

research using phenomenology. This paper is a start.

Figure 1. Relationship of the concepts of personally meaningful,

profound and pleasurable.

One might ask how this discussion relates to other categories of

information behavior, such as leisure. Recall that personal meaning is a

phenomenological description. Over the past several decades, the view of

information science as a social science has predominated (Buckland,

2012). Concomitantly, many concepts in information science can be

understood as sociological descriptions; leisure, and specifically the

serious leisure perspective, are examples. For example, Hartel (2014)

outlines possibilities for information research in the liberal arts

hobbies (forms of serious leisure) taking a social perspective.

A Review of the Literature

To be sure, there is a large body of research examining what amounts to

personally meaningful information activities from a sociological

perspective, though these studies have not yet been theorized in that

way. Studies of information in liberal arts hobbies fit that description

(see Hartel, 2014). That research will not be reviewed here. Rather, I

focus on the smaller body of research that does recognize to some extent

the phenomenological nature of personally meaningful information

activities.

First, at least two other scholars have voiced the need for

phenomenology in this research area. Kari (2007) is one, who, in a

review of the literature on spirituality and information, finds that

identifying "the spiritual" in information has a defining experiential

aspect, though he does not explicitly connect this to phenomenology.

Keilty (2012) does. In an essay on browsing for online pornography,

Keilty remarks that other research has ignored embodiment and

desire—indeed, the lion's share of subjective experience—as aspects

of information behavior. Keilty seeks to remedy that by bringing

phenomenology into the discussion.

Some other research has been attuned phenomenologically to these

questions, with varying degrees of metatheoretical reflection. Some of

this research has focused on information seeking, while some of it has

shed light on the outcomes of information seeking. To speak first of

seeking, Ross' (1999) study on book selection for pleasure reading

certainly bears mentioning. While her study did include some

sociological aspects, she found that people choose books based on

experiences they desire, and that processes of browsing, monitoring and

serendipity play into their discovering new books. Frank (1999) found

that visual artists, too, emphasize browsing in their information

seeking, and Mougenot et al. (2008) likewise describe the information

seeking of designers through personally-curated sets of information

sources as they look for certain moods (which, it bears mentioning, may

not be articulable as a text query). In a different vein, Clemens and

Cushing (2010) present two studies on information seeking in

\"situations involving personal crisis, legal barriers to information,

social stigma and/or significant life-long impact\" (p. 9).

Specifically, they look at mothers who relinquished a child for adoption

in one study and the offspring of sperm donors in a second study. It

should be noted that, though the information seeking in these studies is

personally meaningful, it is not necessarily pleasurable. Indeed, their

results seem to show the negative aspects of these situations, perhaps

because of the social stigma and secrecy involved. Clemens and Cushing

find that existing models of everyday life information seeking do not

capture the particularities of these experiences—unfamiliarity,

isolation and other emotions, and the pursuant coping strategies—but

they do not yet venture to offer a constructive model.

For research on the outcomes of information seeking in personally

meaningful contexts, we can first return to Ross' (1999) study. In

addition to examining how readers select books, Ross looked at people's

experiences of being transformed by books. Ross found that books awaken

new perspectives, model an art of life, offer solace and connection,

etc. Moreover, she found that the practice of reading over the course of

a lifetime shapes one's self. In another study of engaging with

information-as-thing, Latham (2009) studied numinous experiences with

museum objects, uncovering themes: unity of the moment, object link,

being transported and connections beyond the self. To speak of other

outcomes of information, Sköld (2015) presents a study of memory

practices in an online gaming community, wherein people share screen

captures from their game and associated stories as modes of reminiscing

and constructing knowledge. Finally, Tinto and Ruthven (2016) give an

example regarding information sharing; they explored the methods and

factors of sharing so-called happy information (i.e., that which creates

a sense of happiness when shared). Though these practices are rooted in

pleasure, which is at risk of being classified as mere hedonism, Tinto

and Ruthven discuss how sharing happy information can enhance human

relationships, and be shared with that intent, thus constituting deeper

personal meaning than at first may appear.

Research Question

As we have seen, there has been some research in personally meaningful

information activities taking the phenomenological perspective. However,

this research has not yet led to the theorization of personally

meaningful information activities as such. That is, these empirical

results have not yet led to any greater findings. As an illustration, we

can look to the paper by Clemens and Cushing (2010), in which the

findings from the two studies are discussed separately even though they

are, in my view, mutually relevant. This seems to be a missed

opportunity. (They should not be faulted, however, as only so much can

be done in an exploratory conference paper.) A next step, then, in this

research trajectory, is to discover how we can understand the results

from all these studies together. In keeping with the necessary

phenomenological position, in this study I pose the research question:

How do people experience information in personally meaningful

activities?

Methods

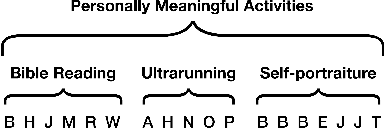

For the past several years, I have been engaged in research on diverse

domains of personal meaning. I conducted one study on Bible reading

among Catholics (Gorichanaz, 2016), another on hobbyist ultra-distance

running (Gorichanaz, 2017), and another on visual artists'

self-portraiture (Gorichanaz, 2018). These studies were conducted,

analyzed and published separately, furnishing empirical findings on each

of these domains. In light of the discussion so far in this paper,

however, there is an opportunity to understand these three studies

together as types of personally meaningful information activities. Thus,

in this study, I analyze anew the empirical material collected over the

years under a single research question.

This study uses interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), an

empirical, phenomenological methodology designed for understanding

particular experiences (Smith, Flowers & Larkin, 2009). IPA has been

used by many scholars in information science to address a variety of

experience-related questions (see VanScoy & Evenstad, 2015). IPA seeks

to value each individual participant's experience while also drawing out

characteristics that are shared across participants. In general, IPA

studies are guided by research questions but not pre-established

theories; through inductive and abductive reasoning, a theory (typically

descriptive) is devised through interpretation from the empirical

material in light of the research question. This theory generally takes

the form of a number of themes that are explicated and linked together

through narrative.

In my study, as is typical of IPA, empirical material was gathered

through semi-structured interviews with individual participants. I

transcribed these interviews and then open-coded each one for emergent

themes that characterize the experience. I did so with each interview.

Then, I considered how each individual's experience does and does not

commensurate with that of the group. Pursuant to IPA, I iterated between

the group and the individuals, allowing themes to coalesce and emerge.

Generally, IPA studies involve only one group of participants. This one,

however, has three groups, and so my analysis involved an additional

stage of comparing the findings from each group to those of all the

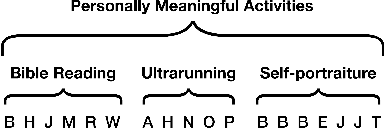

participants together (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Participants and groupings.

{width="5.347222222222222in"

height="1.7777777777777777in"}

{width="5.347222222222222in"

height="1.7777777777777777in"}

The full details regarding recruitment and the participants can be found

in my prior publications (Gorichanaz, 2016, 2017, 2018), so here I will

give only a brief overview. The first group, Bible readers, was

comprised of 6 individuals in Philadelphia who identified as Catholic;

there were 2 men and 4 women, ranging in age from their mid-20s to 60s.

The second group, ultra-distance runners, was comprised of 5 individuals

who participated in a 100-mile footrace that took place in Wisconsin in

2016; there were 3 men and 2 women, ranging in age from their 20s to

50s. The third group, visual artists, was comprised of 7 individuals in

Philadelphia who identified as artists; there were 2 men and 5 women,

ranging in age from 18 to 65. Thus, all said, this study included 18

individuals. IPA studies vary greatly in their sample sizes; the mean

sample size is reportedly 15 participants (Reid, Flowers & Larkin,

2005), though Smith et al. (2009) mention that a group of 3–6 is

sufficient for drawing out meaningful findings and emphasize that the

value of even single-case studies should not be overlooked. In the

present study, the participants in the first (Bible reading) group were

given pseudonyms inspired by herbs; those in the second (ultrarunning)

group were given pseudonyms inspired by the Trojan War; and those in the

third (self-portraiture) group elected to use their real names.

The empirical material in this study come from the interviews I

conducted with these participants. The interviews with the first group

centered around the last time the individual read the Bible; those in

the second group centered around the last 100-mile race the individual

took part in; those in the third group centered around the self-portrait

the individual created as part of my study; in all cases, the interview

also touched on more general matters of information behavior (spanning

needs, seeking and use) regarding the Bible, running and art,

respectively.

Findings

The findings from this study take the form of themes that characterize

the experience of information in personally meaningful activities. The

themes are: identity, central practice, curiosity and presence. Here I

present these themes along with some illustrative quotations from the

participants.

In this paper I will focus on themes that were shared among all or most

of the participants, though they certainly manifested in slightly

different ways across groups and even from participant to participant

within a single group. This contrasts with typical IPA studies, which

generally give equal attention to the particularities of each case and

those aspects of participants' experiences that don't fit into the

themes. I take this approach because the goal of this paper is to draw

lessons for personally meaningful information activities as such, taking

a step back from the idiosyncrasies of each case. More detailed findings

can be found in my prior individual publications on these topics.

Identity

——–

In all cases, the information activities were experienced as part of the

person's identity. That is, doing these activities was inextricable from

who the person is. Concomitantly, the information involved is part of

what makes up that person.

It should be noted that personal identity here can be more granular than

group identity. For instance, though the Bible readers all identified as

members of the community of Catholics, their reading of the Bible was

experienced as a matter of one-to-one engagement with God. Indeed, most

of the participants expressed that Bible reading is not a typical

activity for Catholics.

Another note of interest is that in most cases, the activity was not

part of the person's identity for their whole life; rather, it is

something that they discovered at some point and cultivated as a

personally meaningful activity to the extent that it now forms part of

their self-concept. Helen's account of running illustrates this

poignantly:

I started running about 7 years ago, just to get out of the house,

really. I had two little children, and I was pushing them in the

stroller and just trying to get some space in my head to think. I

always noticed I was pushing them as fast as I could, and then I just

started gradually running. It just grew. You think you can't do it,

and you start running from one sign to the next, and then you enter a

race.

Helen, like the other runners, described her trajectory in terms of

taking on progressively greater challenges. Similarly, the Bible readers

conceptualized their practice as "a journey." For the artists, this

journey was a matter of developing their personal style through

deliberate practice and experimentation.

Central Practice

—————-

The information activities in this study involved a central practice

along with a number of periphery activities that supported or enhanced

it. Bible readers, for example, not only read the Bible, but also read

commentaries and meditations on particular passages and also conduct

searches for additional information (e.g., historical context). Runners

not only run races and training runs, but also read race reports and

magazines, engage in social media discussions, and research new products

to support their running. Artists not only create particular artworks,

but also doodle, read widely and monitor social media for inspiration.

These periphery practices come to bear on the central practice,

sometimes in unexpected ways. For example, during the months when Justin

was working on his self-portrait, a photographer visited his studio for

a photo shoot, and soon after he went on a hiking trip to Colorado to

experience the full solar eclipse. These events unexpectedly affected

his self-portrait. As he explains:

It took me a while since our initial meeting to formulate what I

wanted to do. I sat on it for a while, just thinking. I would say

months and months of thought went into the initial concept of it. The

length of time from concept to finish even then was a few months. I

was putting—not pressure, but... I took this trip to Colorado, and

then these photoshoots, seemed to motivate me to finish it while I had

this idea of who I am and what I'm trying to do, if that makes any

sense. That pushed it over the edge for me to really finish it,

because it was very fresh, my point of view of myself was so fresh,

and the artwork showed. Like it went from slow concept build to the

attempts and once those photoshoots happened and this trip I took that

seemed to be very important to me, as soon as I got back it was done

within that week. [...] It gave me the confidence as an artist and

to achieve my goal. I had a goal to climb that mountain, and I

achieved it. And that gave me the confidence to trust my instincts on

it and use what I did, and have the confidence that it was gonna be

fine and that I was gonna be satisfied with it. [...] And the

perception of it, I was concerned about the perception of how other

people would look at it and see me as, but once that trip happened,

that went away, if that makes sense.

This demonstrates that, though these information activities can be

analytically isolated and conceptualized, they are always playing out in

the lifeworld, and they can be enriched, challenged, replaced, etc., by

other goings-on. To speak of replacement, Emily's account provides a

good example; she began her self-portrait as a photographic collage, but

as the months passed she left photography behind and moved to oil

painting. Her painting was restarted many times, and she stopped to work

on other paintings throughout the process as inspiration struck her.

Curiosity

———

All the participants were guided in their information activities by

curiosity. This is not curiosity in Heidegger's (1927/2010) sense of

curiosity as "lust for the new," but rather a focused curiosity, wherein

the participants let themselves wander with respect to a particular

topic or question. This involved regularly monitoring certain

information sources, ranging from Facebook and Pinterest to daily

devotional texts, and seeking further information on topics that sparked

the person's interest. Oftentimes this was a matter of being open to

engaging with the information that is already tacit in the person's

lived experience. This is an openness to being informed, or in-formed.

This was conceptualized in various ways; for instance, the artists

talked about this as finding inspiration, whereas the Bible readers

talked about it as being guided by God. As Willow put it:

I always think the Lord leads you, because you'll read something, and

He leads you to that, and then you start investigating, and you read

more, and you go deeper and deeper ... And it takes you to another

scripture ... It's like a little journey.

Following one's curiosity in these personally meaningful activities led

to a personal progression which was, generally, transparent to the

person. The Bible readers described their engagement with the Bible as

central to their "journey" in life. All my participants in the Bible

study were born and raised Catholic, but they went through periods of

little interest in religion, typically beginning in the teenage years

and lasting for a decade. In their case, their journey seems to be a

matter of blooming faith; within this, participants cultivated an

appreciation for the ritual, a deeper relationship with God, and inner

peace. For the ultrarunners, this progression took the form of

continually growing challenges. As an ultrarunner grows in their

athletic career, they typically pursue longer races, faster times,

and/or new settings.

Nestor described this well in his interview:

I definitely want to continue reaching higher and higher. There is a

quote that really resonated with me, and I've got it posted on my wall

at home. It's from that book Born to Run, and there's a section in

it that says, "Why the hell would you run a 100 mile race?" and the

guy's response was, "Why does anybody ever climb Everest? It's because

it's there." So the quote on my wall is "Because it's there." I'm here

right now. So what else can my body do? What's actually possible? How

far can I push myself? What are my actual limits? Continuing to find

those and continuing to improve. What am I absolutely capable of?

As for the artists, their progression entailed developing and exploring

their personal style, gaining skill with their chosen media, and trying

new techniques and materials. For the professional artists, an important

part of their progression was becoming financially independent as

artists.

Of course, this progression is not a journey in the sense of having had

a destination predetermined from the outset. Rather, it is a cumulating

response at every juncture, taking into account where one has already

been and the present situation. The trajectory can only be seen in

hindsight; as Kierkegaard wrote in one of his journals, \"Life can only

be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards."

Presence

——–

Finally, all the participants expressed that presence is an essential

aspect of their personally meaningful activities. Indeed, they made

choices with regard to information technology that encouraged them or

helped them to be more engaged in the present experience. For example,

the Bible readers described conscientiously using print versions of the

Bible when their goal was meditation and prayer, whereas a digital

version may suffice if they were, say, looking for the wording of a

particular passage. Jasmine said:

The biggest difference with me is when I'm sitting there with the hard

copy and it's in my private time with the Lord, I feel much more

relaxed. Much more like we're there together. When I'm on this thing

[gesturing to her phone], it's like, "Okay, be quick." I get

distracted easily. If I'm on the computer at work, say, and we're

talking, and I say, "Wait, wait, let me look that up." But then,

"Okay, wait, I gotta get this," and, "Oh, yeah, can I help you?" When

I'm there with the hard Bible ... it's just me and Him. I don't find

it so on the electronics. I'm distracted more easily.

The runners, too, made judicious use of technology so as to enhance

their running experience with respect to their goals. Today, there are

any number of gadgets available for runners' self-tracking of heart

rate, cadence, speed, distance, altitude, etc., and for listening to

music, podcasts or other programming, all of which modulate the running

experience. The ways in which the various gadgets constrain or afford

presence seem, to some extent, to be personal. For instance, Ajax

expressed that any technology was a distraction and he prefers to "run

by feel," whereas Nestor and Odysseus found that using a heart rate

monitor helped them stay attuned to their body and remain more present.

Both Nestor and Odysseus contrasted the heart rate monitor with GPS

tracking, which they found to be a distraction. As Odysseus said:

I don't find a GPS to be helpful because I'm much more in tune with

how I feel. If I had a GPS and I start paying attention to my GPS

splits, I find it much harder to maintain an appropriate pace and much

easier to overdo it, because I want to hit that 8-minute mile here and

maintain it when my body is telling me don't do that.

As for the artists, they seemed to choose materials and work situations

that helped them be more present in their art-making. In some cases they

carved out time from their daily schedules in order to make art, and

they did so in places where they wouldn't be interrupted. Again, these

decisions are personal. Brianna, for instance, found that she was most

productive in art-making late at night in her home studio, where and

when she wouldn't be bothered by other people or be distracted by other

obligations later in the day. Emily specifically described her artistic

practice as "very slow and meditative," by choice. For her and the other

participants from all three groups, the personally meaningful activity

was seen as a respite from the rest of daily life.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study has conceptualized personally meaningful information

activities and presented an investigation into some of their

phenomenological themes. As I have described in the previous section,

personally meaningful activities play a role in a person\'s development

of their identity, or self-concept. This identity coheres over time,

through a personal progression which is guided by a focused form of

curiosity, which continually brings new elements into a central

practice. This central practice is characterized by by presence. Thus we

can see how these themes are linked together and overlap, though they

were analytically separated for the purposes of presenting the findings.

Though, as I have discussed in the literature review, personally

meaningful information activities have not yet been conceptualized or

investigated as such, there has been some relevant research, and the

present study seems to corroborate those findings while also bringing

them into context around the concept of personally meaningful

information. Ross (1999), for example, found a form of focused curiosity

in her readers. As Ross says, readers are open to their environment for

new reading possibilities and connections, and some reading material

contributed to one's sense of identity. On the note of identity, Clemens

and Cushing (2010) found that information sought in emotional and

personal situations comes to be part of one's identity. As their

participant Kate said, "I'm searching for answers in my own identity"

(Clemens & Cushing, 2010, p. 9). Considered from a more general

philosophical perspective, this demonstrates Floridi's (2013) assertion

that you are your information. Additionally, the theme of presence seems

to have surfaced in Latham's (2009) study of numinous experiences in

museums as her theme of unity of the moment. As she indicates, there is

more to presence than just the present moment; presence is the

experience that the past, present and future are coextensive and in

harmony. In my study, this is perhaps best seen in the art-making

experience of Brian, who, in a meditative state, conjured memories from

the past, processed them, and brought them forward materially into his

artwork, bringing him to his next move.

In addition to conceptualizing personally meaningful information

activities, this study contributes to information behavior theory more

generally. Like some other studies, it presents a challenge to the idea

that information seeking is necessarily problematic and negative (see

Kari & Hartel, 2007). However, this study also complicates dualistic

discussions of emotional valence. It is tempting to think in terms of

positive and negative: good/bad, happy/sad, etc. Recognizing the concept

of meaningfulness in information behavior is a reminder that lived

situations are not that simple. It is in this vein that Baumeister

(2005) differentiates meaning from happiness; having personal meaning

does not necessarily entail happiness. A quotation from filmmaker Hayao

Miyazaki illustrates this well: "I don't ever feel happy in my daily

life. Really, isn't that how it is? How could that ever be our ultimate

goal? Filmmaking only brings suffering. I can't believe I actually want

to do another one" (Kawakami & Sunada, 2013).

All this has a number of implications for technology. Tacitly, we seem

to assume that technology should make things easier for people. As I

have written previously on the topic of building understanding, this may

not always be for the best (Gorichanaz, 2016). Just as with building

understanding, it may turn out to be necessary to slow down and undergo

struggle to cultivate deep personal meaning. If meaning is truly an

essential aspect of human life, as many thinkers contend, then

technologists should engage with the question of how particular

technological interventions contribute to or detract from opportunities

for meaning. Indeed, meaning is not a given, but something that is

consciously cultivated. We are beginning to see effects of technologies

that ignore the essential nature of meaning. For example, a

psychological study by Verduyn et al. (2015) suggests that aimlessly

browsing social media undermines well-being; in the context of my

discussion here, this is because the aimless activity is meaningless. In

contrast, finding meaning in one's life has been associated with

positive well-being (Zika & Chamberlain, 1992). More recent research

has, moreover, supported the hypothesis that personal meaning indeed

leads to positive well-being (García–Alandete, 2015). We have seen

that personal meaning is somewhat idiosyncratic; however, it is not

totally random and inscrutable. The themes of identity, central and

peripheral practice, curiosity and presence described in this paper

provide a locus for developing technologies that encourage the

cultivation of meaning.

The findings of this study also set the stage for further research. Van

Manen (2014, p. 29) reminds us that "Phenomenology is primarily a

philosophic method for questioning, not a method for answering or

discovering or drawing determinate conclusions." That is, the present

study is valuable insomuch as it sparks further research questions.

Future research should explore other sorts of personally meaningful

information activities in a continued attempt to discern what it is

about them that makes them so. Additionally, research can look more

deeply at particular aspects of information behavior (e.g., seeking) or

particular slices of information practices for a more granular look,

whereas this study has cast a wide net for understanding.

References

Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Meanings of life. New York: Guilford Press.

Baumeister, R. F. (2005). The cultural animal: Human nature, meaning,

and social life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Buckland, M. K. (2012). What kind of science can information science

be? Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 63(1),

1–7. doi: 10.1002/asi.21656

Budd, J. M. (1995). An epistemological foundation for library and

information science. Library Quarterly, 65(3), 295–318.

Budd, J. M. (2005). Phenomenology and information studies. Journal of

Documentation, 61(1), 44–59.

Cafaro, P. (2004). Thoreau's living ethics: Walden and the pursuit of

virtue. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Capurro, R. (2000). Ethical challenges of the information society in the

21st century. The International Information & Library Review, 32,

257–276.

Clemens, R. G., & Cushing, A. L. (2010). Beyond everyday life:

Information seeking behavior in deeply meaningful and profoundly

personal contexts. Proceedings of the American Society for Information

Science and Technology, 47(1), 1–10.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Beyond boredom and anxiety: Experiencing

flow in work and play (25th anniversary edition). San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass. (Original work published 1975)

Dreyfus, H., & Kelly, S. D. (2011). All things shining: Reading the

Western classics to find meaning in a secular age. New York, NY: Free

Press.

Floridi, L. (2011). The philosophy of information. Oxford, UK: Oxford

University Press.

Floridi, L. (2013). The ethics of information. Oxford, UK: Oxford

University Press.

Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the self. In L. H. Martin, H.

Gutman, & P. H. Hutton (Eds.), Technologies of the self: A seminar with

Michel Foucault (pp. 16–49). Amherst: University of Massachusetts

Press.

Frank, P. (1999). Student artists in the library: An investigation of

how they use general academic libraries for their creative needs.

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 25(6), 445–455.

Frankl, V. (2006). Man's search for meaning: An introduction to

logotherapy (I. Lasch, Trans.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press. (Original

work published 1946)

García–Alandete, J. (2015). Does meaning in life predict psychological

well-being? The European Journal of Counselling Psychology, 3(2),

89–98.

Gorichanaz, T. (2016). Experiencing the Bible. Journal of Religious and

Theological Information, 15(1/2), 19–31.

Gorichanaz, T. (2017). There's no shortcut: Building understanding from

information in ultrarunning. Journal of Information Science, 43(5),

713–722.

Gorichanaz, T. (2018). Understanding self-documentation (Unpublished

PhD dissertation). Philadelphia, PA: Drexel University.

Hadot, P. (1995). Philosophy as a way of life (A. I. Davidson, Ed. &

M. Chase, Trans.). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hammell, K. W. (2004). Dimensions of meaning in the occupation of daily

life. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(5), 296–305.

Harré, R. (1998). The singularity of the self: An introduction to the

psychology of personhood. London, UK: Sage.

Hartel, J. (2014). An interdisciplinary platform for information

behavior research in the liberal arts hobby. Journal of Documentation,

70(5), 945–962.

Heidegger, M. (2010). Being and time (J. Stambaugh, Trans.). Albany:

State University of New York Press. (Original work published 1927)

Kari, J. (2007). A review of the spiritual in information studies.

Journal of Documentation, 63(6), 935–962.

Kari, J., & Hartel, J. (2007). Information and higher things in life:

Addressing the pleasurable and the profound in information science.

Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 58(8),

1131–1147.

Kawakami, N. (Producer), & Sunada, M. (Director). (2013). The kingdom

of dreams and madness [Motion picture]. Tokyo, Japan: Toho Company.

Keilty, P. (2012). Embodiment and desire in browsing online pornography.

In J.-E. Mai (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2012 iConference (pp. 41–47).

New York, NY: ACM. doi: 10.1145/2132176.2132182

Latham, K. F. (2009). Numinous experiences with museum objects

(Unpublished PhD dissertation). Emporia, KS: Emporia State University.

Mills, C. W. (1953). White collar: The American middle class. New

York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mougenot, C., Bouchard, C., & Aoussat, A. (2008). Inspiration, images

and design: A field investigation on information-retrieval strategies by

designers. Journal of Design Research, 7(4), 331–351.

Newport, C. (2016). Deep work: Rules for focused success in a

distracted world. New York, NY: Grand Central Publishing.

Nicholson, D. (2002). The "information-starved"—Is there any hope of

reaching the "information super highway"? IFLA Journal, 28(5–6),

259–265.

Peterson, J. B. (1999). Maps of meaning: The architecture of belief.

New York, NY: Routledge.

Reid, K., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2005). Exploring lived experience.

The Psychologist, 18(1), 20–23.

Ross, C. (1999). Finding without seeking: The information encounter in

the context of reading for pleasure. Information Processing &

Management, 35(6), 783–799.

Savolainen, R. (1995). Everyday life information seeking: Approaching

information seeking in the context of "way of life." Library &

Information Science Research, 17(3), 259–294.

Schiller, F. (2004). On the aesthetic education of man (R. Snell,

Trans.). Mineola, NY: Dover. (Original work published 1795)

Sköld, O. (2015). Documenting virtual world cultures: Memory-making and

documentary practices in the City of Heroes community. Journal of

Documentation, 71(2), 294–316.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative

phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, research. London, UK: Sage.

Tinto, F., & Ruthven, I. (2016). Sharing \"happy\" information. Journal

of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(10),

2329–2343.

Vamanu, I., Gorichanaz, T., Latham, K. F., & Suorsa, A. (2016).

Phenomenology in library and information science: Studying information

experiences. Panel presented at Conceptions of Library & Information

Science, Uppsala, Sweden.

Van Manen M. (2014). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods

in phenomenological research and writing. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast

Press.

VanScoy, A., & Evenstad, S. B. (2015). Interpretative phenomenological

analysis for LIS research. Journal of Documentation, 71(2), 338–357.

Verduyn, P., Lee, D. S., Park, J., Shablack, H., Orvell, A., Bayer, J.,

Ybarra, O., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2015). Passive Facebook usage

undermines affective well-being: Experimental and longitudinal evidence.

Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(2), 480-488.

Wiener, N. (1954). The human use of human beings: Cybernetics and

society. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Wright, H. G. (2016). Ontic ethics: Exploring the influence of caring

on being. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Zika, S., & Chamberlain, K. (1992). On the relation between meaning in

life and psychological well-being. British Journal of Psychology,

83(1), 133–145.

{width="5.347222222222222in"

height="1.7777777777777777in"}

{width="5.347222222222222in"

height="1.7777777777777777in"}